Hearts are for love on Valentine’s Day

10 February, 2026

By Dr Claire Hilton, Honorary Archivist at the RCPsych.

Expressions of human emotion have been linked with the heart for centuries, including in the Bible, Quran and other religious and classical texts. Heart-felt emotions may include love, but we also have heart-break, or we may be half-hearted, open-hearted or heartless. Some traditional sources use the term ‘diseases of the heart’ to mean emotional, moral or spiritual disorders. Those mentioned, for example, in Islamic texts, include arrogance and conceit; ostentation; anger; and love of power, position, and fame. Some may be fatal if not attended to.

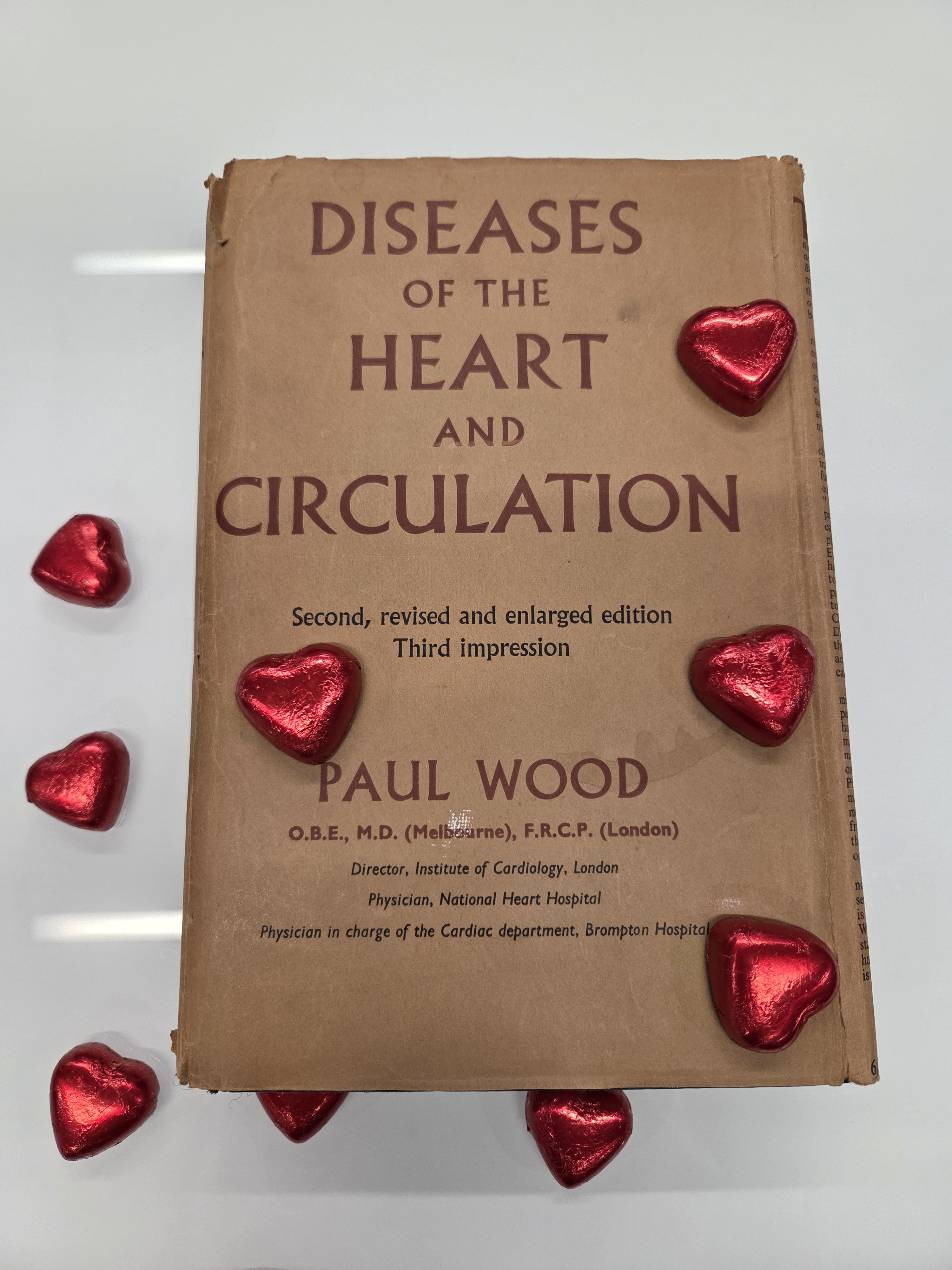

Photograph by Fiona Watson, RCPsych Librarian.

Today we understand the physiological links between the brain, autonomic nervous system and heart, and that strong emotions may alter the heart rate, such as with anxiety. There are, of course, endless physical pathologies which can affect the heart, which may be as mysterious to a psychiatrist as psychiatric states are to a cardiologist.

Today is Valentine’s Day so we have a textbook of cardiology in the Cabinet of Curiosities. It is Paul Wood’s Diseases of the Heart and Circulation (2nd edition, 1956). For Wood, Diseases of the Heart were biological, except in the final chapter of his book, ‘Cardiovascular disturbances associated with psychiatric states’. There he referred to ‘anxiety states or…almost anything with high emotional content’, and continued the chapter by describing his research on cardiac symptoms and anxiety, undertaken collaboratively with some leading mid-twentieth century British psychiatrists and psychologists. The book brought the author ‘worldwide recognition as the European authority on heart disease‘.

You might ask why the RCPsych has a copy. The short answer is that it was among the books donated to the College in 2025 from the library of the late Professor Sir David Goldberg. The long answer relates to the final chapter.

Paul Wood and Effort Syndrome, 1939-41

During the early part of the Second World War, cardiologist Paul Wood and psychiatrist Maxwell Jones jointly ran the Emergency Medical Service Effort Syndrome Unit at Mill Hill, part of the evacuated Maudsley Hospital. Relocated to the northwest London suburbs, it was relatively safe from the bombing, but it still needed, and used, its air-raid shelters.

An eerie light at the foot of the stairs leading into the abandoned air raid shelter behind the Infirmary Block of the Mill Hill Maudsley (photo by author, 2025)

Serving both military and civilian patients, the Mill Hill Maudsley had an eminent multi-disciplinary staff team, including Annie Altschul, Hans Eysenck, Eric Guttman, Aubrey Lewis, Felix Post, John Raven and Elizabeth Rosenberg.

Effort syndrome presented with symptoms including heart palpitations, shortness of breath, fatigue, and dizziness, all symptoms which could limit a patient’s ‘capacity for effort’. It was a condition long-recognised, and had a multiplicity of other names, such as ‘Da Costa’s syndrome’, ‘soldiers’ heart’, and ‘disordered action of the heart’. During the First World War, approximately 60,000 cases of effort syndrome were reported amongst British Forces. At that time, understanding the balance between possible physical and mental causes and methods of treatment was still unclear. Treatments varied: some doctors prescribed complete bed rest, and others argued that hospital stays should be kept short, as these were seen as potentially harmful due to the lack of discipline and its effect on a soldier’s morale. Typically, treatment focussed on gradually building up tolerance to physical effort, to help reassure the sufferer that their heart was normal. It did not, however, take a broader psychological approach to help the person understand why they were suffering in that way.

Wood’s research pointed to effort syndrome being psychological, the same as ‘cardiac neurosis’, a condition occurring commonly in civilian life especially among women, the two distinguished only by being ‘merely clothed differently, the former in battle dress, the latter in nylon’ (pages 937-8: the first edition says ‘artificial silk’ p.535-6—he obviously wanted to be up-to-date with the latest clothing fashion). Wood’s initial research findings appeared in the BMJ in 1941 (24 May, p.767-72; 31 May, p.805-11; 7 June, p.845-51), and he recommended treatment by psychiatrists, not cardiologists.

Wood’s chapter included a case study:

a patient at Mill Hill gave a history of a morbid fear of fireworks in his boyhood, conditioned by London air raids in his infancy. Otherwise he was fit and strong. He was called up in September 1939, was sent to France, and remained well until told one day to unload an ammunition lorry. On handling the shells he became curiously panic stricken, developed gross psychosomatic symptoms, and mis-interpreted them, thinking they meant heart disease. A vicious circle was initiated, he reported sick, and finally arrived at a base hospital with an established ‘effort syndrome’. When the link between his fear of handling fireworks and his handling of shells for the first time was pointed out, he was suddenly convinced of the truth of the explanation given for his symptoms and made a rapid and complete recovery [from the cardiac symptoms]. But his fear of fireworks, shells and all other explosives was unabated. Treatment had only been directed towards the removal of effort intolerance, by abolishing the misinterpretation and vicious circle that initiated and maintained it.

Once he appreciates the fact that if he no longer fears his symptoms he will cease to aggravate them, the point is scored……[but the] methods so far outlined do not touch the underlying psychoneurosis, and the real treatment has yet to begin.…

At Mill Hill, treatment initially included education sessions on physiology and anxiety, but when it became clear to Jones that patients were more concerned with their impending military service than the science behind their mental state, he introduced more discussion. Patients raised social issues in those discussions, such as about morale, ward life and external stresses, and nurses who attended the discussions took more interest in these concerns. Gradually the ‘therapeutic community’ concept was formulated, of a psychologically informed social environment, where relationships and activities were designed to promote health and well-being, with treatment being ‘a continuous process operating throughout the waking day and over every aspect of the life of the patient.’

Although the Wood-Jones collaborative study ended in 1941, the Effort Syndrome Unit continued throughout the war, and Maxwell Jones’ therapeutic community legacy continues into the present.

Happy Valentine’s Day!

Further reading: Maxwell Jones, Social Psychiatry: A Study of Therapeutic Communities, London: Tavistock Publications, 1952.