Alcohol, mental health and the brain

This resource looks at alcohol and how it can affect your brain and mental health. It is aimed at adults who want to learn more about alcohol, who are dependent on alcohol or who know someone who is.

This information looks at:

- What alcohol is

- How it affects the brain

- How it affects mental health

- Alcohol dependence

- Alcohol-related brain damage

- How to work out how much you drink

- How to get help if you are drinking too much

About our information

We publish information to help people understand more about mental health and mental illness, and the kind of care they are entitled to.

Our information isn't a substitute for personalised medical advice from a doctor or other qualified healthcare professional. We encourage you to speak to a medical professional if you need more information or support. Please read our disclaimer.

Alcohol (also known as ‘ethanol’ or ‘ethyl alcohol’) is a substance that once absorbed into the blood stream can enter every organ of the body.

Drinks containing alcohol are called alcoholic drinks. There are lots of different kinds of alcoholic drinks, which are produced in different ways and contain a range of other ingredients. However, they generally fall into the following categories:

- beer and cider

- wine

- spirits (such as vodka, gin or whiskey)

Different alcoholic drinks contain different ‘strengths’ of alcohol. This means that some alcoholic drinks have more of an effect on the body than others.

It is legal for adults over the age of 18 to buy and drink alcohol in the UK. Generally, it is illegal for young people under 18 to drink or buy alcohol. You can find out more about the laws around alcohol on the Government website.

Why do people drink alcohol?

In a study of people in England from 2021, just under half of the people who were asked said that they drank alcohol at least once a week.

People drink alcohol for lots of different reasons. Some people drink alcohol for fun, or to relax. Other people drink alcohol to help them to deal with difficulties in their lives.

Alcohol affects people in different ways. Some people find that they can drink alcohol occasionally and enjoy doing so, and that it doesn’t have a negative effect on them. Other people struggle not to drink too much, or do things that they regret when they drink.

Some people choose not to drink alcohol at all. This can be for lots of different reasons, including:

- they don’t like feeling drunk

- they don’t like the taste

- it makes them feel sick or very sleepy

- to support their health

- for religious reasons

And some people just choose not to drink.

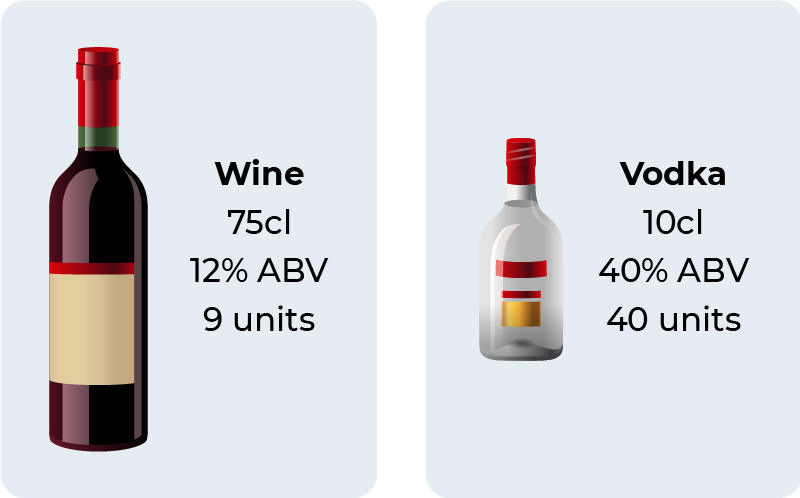

There are two ways to tell how strong alcoholic drinks are:

- Units – Units were developed to make it easier for people to work out how much they are drinking. Units are measured differently in different countries. In the UK one unit is 10ml (or 8g) of pure alcohol.

- Alcohol by volume, or ABV – This means how much pure alcohol is in an alcoholic drink.

Example

You have a 750ml or 75cl bottle of wine. The bottle says it is 12% ABV, which means the bottle is 12% pure alcohol. This bottle of wine contains 9 units.

There is no ‘safe’ level of alcohol consumption, as everyone’s bodies work differently. You can never know exactly how alcohol will affect you.

Adults who drink alcohol are advised to limit the risks of harm by drinking no more than 14 units of alcohol over the course of a week. This is equivalent to:

- 5 pints of under 3% ABV beer or

- 10 small (125ml) glasses of 12% wine.

These units should be spread over the week, with days in between where you don’t drink.

All people should try to avoid ‘binge drinking’. This means drinking over 8 units in one day for men, and over 6 units in one day for women.

How can I avoid drinking too much?

If you think you might be starting to drink too much, and would like to be more in control of how much you drink:

- Set yourself targets to reduce how much you drink over time.

- Avoid spending time with people or in environments that encourage you to drink more.

- Drink lower-strength drinks, such as low or no alcohol beers or wines.

- Think of activities you can do that don’t involve drinking alcohol.

- Involve your partner or a friend. You can agree a goal together and keep track of your progress, using the alcohol tracker at the end of this resource.

- Talk it over with your GP. For many people this simple step helps them to cut down their drinking.

When setting goals for controlling your drinking, try to make them specific, easy to measure, achievable, realistic, and give yourself a timeframe within which to do them. This will make you more likely to achieve your goals.

As we get older, our bodies change and break down alcohol more slowly. This can make older people more sensitive to the effects of alcohol.

There are some things that can mean drinking alcohol is more dangerous in older people, including:

- Health problems – Older people are more likely to have other health problems. This can make them more susceptible to the effects of alcohol.

- Risk of falls – Usually, as we get older our reaction times and balance get worse. Alcohol can make you more unsteady, and so older people might be more likely to have falls when they drink.

- Medications – There are some medications that are more commonly used by older people which can interact with alcohol and be dangerous. For example, if you drink alcohol and are taking medications to thin your blood, this can increase your risk of bleeding if you are injured. And if you drink alcohol while taking certain antibiotics, this can make you feel very sick.

- Forgetfulness – Sometimes as people get more forgetful, or develop dementia, they forget how much alcohol they are drinking. If this happens to you, you might increase the amount that you are drinking without realising it.

Choosing whether or not to drink alcohol is a personal decision. It will depend on lots of different factors. If you are worried that alcohol is affecting your health, or that it might interact with your medication, speak to your GP.

Alcohol affects how brain chemicals called ‘neurotransmitters’ work. The main neurotransmitters affected by alcohol are GABA and Glutamate. These work in opposite ways.

- GABA ‘calms’ the brain and body. Alcohol increases the effect of GABA, so at low levels alcohol can make you feel calmer, or less anxious.

- Glutamate ‘stimulates’ the brain and body. Alcohol decreases the effect of Glutamate, so drinking alcohol can make you feel less alert.

Drinking alcohol can have a negative effect on your mental health in different ways:

- If you drink a lot, or drink every day, this can have a negative effect on your mood as time goes on. You can find out more about why this is further on in this resource.

- If you have problems with your mental health, or have been diagnosed with a mental illness, drinking alcohol can make this much worse. Drinking alcohol can also increase your risk of self-harm and suicide.

- If you have a pre-existing mental health problem, you might drink alcohol to try and feel better. However, this can have the opposite effect.

Why does alcohol affect mental health?

There are a number of reasons why drinking alcohol can negatively affect your mental health, including:

- Brain chemistry - Alcohol affects the chemistry of the brain, increasing the risk of depression, panic disorder and impulsive behaviour.

- Hangovers - If you have a hangover, it can make you feel ill, anxious and jittery. If this happens all the time, it can have a negative effect on your mental health.

- Life challenges - If you develop a problem with alcohol, your life can get more difficult. Drinking might affect your relationships, work, friendships or sex life.

Will my mental health improve if I stop drinking or cut down?

Generally, cutting down or stopping drinking can have a positive effect on your mental health. If drinking has been making you feel bad, after a few weeks of not drinking you might start to feel better physically and mentally. However, the relationship between alcohol and mental health is complicated, especially for people who have experienced trauma and need help to deal with underlying challenges so they can stop using alcohol.

If you have struggled to stop using alcohol, or if alcohol is making your mental health worse, talk to your GP. There might be another reason that you are experiencing mental health problems, and you might need more help. For example, through a psychological therapy or medication.

Can I drink alcohol if I have an existing mental illness?

If you have a mental illness or are struggling with your mental health and do not currently drink alcohol, the best thing to do is not to start. Drinking alcohol if you have a mental illness can have a negative effect on your mood and potentially make your problems worse. It can also interfere with certain medications.

If you already have a mental health problem, or have been diagnosed with a mental illness, speak to your GP about the impact drinking alcohol might have on you. If you are taking certain medications, your GP might advise you not to drink alcohol.

Alcohol can have positive effects. At low levels, it can make you feel:

- happy

- calm

- talkative

- confident.

Alcohol can also have embarrassing or potentially dangerous effects, including causing you to:

- feel sleepy

- become clumsy

- have slurred speech.

The more alcohol you drink, the more it can affect your self-control and judgement. This might mean that you:

- do things you wouldn’t normally do

- say things you wouldn’t normally say

- do dangerous or reckless things

- forget what you did when you were drinking alcohol

- have a hangover the next day.

Alcohol affects people in different ways. Some people find that these things happen even when they don’t drink frequently or in large amounts.

Hangovers

A hangover happens when you have been drinking and stop, and the level of alcohol in your body decreases. This happens a few hours after you have stopped drinking, but you might not notice it until you wake up. If you have a hangover, you might find that:

- your head hurts

- you feel sick

- you have difficulty sleeping

- you feel irritable and anxious.

These feelings are caused by alcohol and the other chemicals in alcoholic drinks making you dehydrated and causing your blood sugar to fall.

There is no way to completely get rid of a hangover. However, you should drink water and avoid drinking alcohol again until your body has had time to recover properly.

If you don’t get hangovers when you drink, this is not necessarily a good thing. Not getting hangovers can be a sign that your body has got used to you drinking a lot, and might mean that you have become dependent on alcohol.

Blackouts

A blackout happens when you drink a lot within a short space of time, and are unable to remember what happened while you were drunk. You might not remember what you said or did, or even where you were. During a blackout you might do things that you later regret, end up in dangerous situations, or risk being harmed by other people.

Blackouts happen because the alcohol has stopped your brain from making new memories. A blackout is a warning that you are drinking too much. It is also an early sign that alcohol is damaging your brain and that you might be alcohol dependent.

Alcohol poisoning

Alcohol poisoning happens when you drink so much that the level of alcohol in your body becomes dangerous. Alcohol poisoning can slow your breathing, cause you to become unconscious or have a fit, and can be fatal.

The NHS website has a list of signs that you or someone you know might have alcohol poisoning.

If you think you or someone you know has alcohol poisoning, call 999 immediately.

Alcohol and the body

If you drink a lot of alcohol or drink frequently for a long time, you are at a higher risk of:

- physical injury

- high blood pressure

- heart failure

- stroke

- pancreatitis – this is where the pancreas becomes inflamed and damaged

- liver disease – alcohol-related liver disease happens in stages. It can lead to the liver becoming permanently damaged and scarred

- cancers, including liver, mouth, head and neck, breast and bowel cancer

- sexual problems like impotence or premature ejaculation

- infertility

- brain damage – see the section on alcohol-related brain damage further on in this resource

Alcohol dependence

Alcohol dependence is also known as alcohol addiction, or alcoholism. Being dependent on alcohol is sometimes referred to as being ‘an alcoholic’. Some of these terms are considered stigmatising by some people.

Around 1 in 100 adults in the UK are dependent on alcohol. If you are dependent on alcohol, you might:

- feel a strong urge to drink alcohol

- struggle to control how much you drink

- continue to drink even if it has a negative effect on your life.

You don’t have to drink a certain amount of alcohol or drink all the time to be dependent on alcohol.

Some people who are dependent on alcohol will also have physical symptoms including:

- Becoming tolerant to alcohol - If you regularly drink a lot of alcohol, over time your brain will become less responsive to its positive effects. You will need to drink more or stronger alcohol to get the same effects that you used to. This means you have become ‘tolerant’ to alcohol.

- Withdrawal symptoms – If you are dependent on alcohol, this will change the balance between GABA and glutamate neurotransmitters in your brain. This means that if you suddenly stop or cut down your drinking, your brain will overreact. This can make you anxious, irritable, shaky and sweaty. These are called withdrawal symptoms.

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome happens when someone stops drinking alcohol when they have been drinking a lot for a long time.

It usually starts within one or two days after stopping drinking, and lasts for up to three days.

People with alcohol withdrawal syndrome will experience some of the following physical symptoms:

- shaking

- feeling sick

- difficulty sleeping

- a racing heart

- high blood pressure

- seizures

And some of the following mental symptoms:

- fear

- depression

- agitation

- hallucinations (seeing, feeling or hearing things that aren’t there)

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome is a serious medical condition. If you have any of the symptoms above, you should seek help from your GP or other healthcare professional.

How is alcohol withdrawal syndrome treated?

How alcohol withdrawal syndrome is treated will depend on how severe it is. Some people will be able to stop drinking without medical treatment. However, others will need professional treatment and support if their withdrawal symptoms are moderate or severe.

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome can be treated with a drug called a benzodiazepine. If you have alcohol withdrawal syndrome, you would be given a course of benzodiazepines for several days, or until your withdrawal symptoms have stopped.

Your benzodiazepine dose should then be slowly reduced before being stopped entirely. This is because benzodiazepines are addictive when taken for a long time.

Some people will need to go into hospital to be treated for alcohol withdrawal syndrome.

Delirium tremens (also called DTs) is a serious and dangerous complication of alcohol withdrawal. ‘Delirium’ describes a state of disorientation, which often includes hallucinations and delusions. ‘Tremens’ describes the tremors or shakiness that happen when someone is withdrawing from alcohol.

Delirium tremens is a medical emergency. There is always a risk that someone with delirium tremens can die. People who have delirium tremens should be admitted to hospital for immediate medical support.

What are the symptoms of delirium tremens?

If you have delirium tremens you will have some of the symptoms of alcohol withdrawal syndrome, and:

- struggle to understand what is going on around you

- not know where you are, why you are there or what time it is

- see or hear things that are not there, e.g. small animals or insects, noises or voices

- feel as though you are in danger

- feel frightened or act aggressively

Delirium tremens is very dangerous, and can cause:

- dehydration

- chemical imbalances

- strain on the heart

- a lowered resistance to infections.

How is delirium tremens treated?

If you have delirium tremens, you need to be admitted to hospital. Here, you will be offered treatment to reduce the severity of alcohol withdrawal. This will usually be a benzodiazepine.

Alcoholic hallucinosis is where you hear sounds, voices or music when you aren’t drunk or haven’t suddenly stopped drinking. It can happen if you drink regularly and become dependent on alcohol. This is different to delirium tremens. Alcoholic hallucinosis can continue even after you stop drinking.

Alcohol-related brain damage (ARBD) can happen if you drink at high levels, daily for a long time.

Studies suggest that as many as 3 in 10 people who are dependent on alcohol could have ARBD.

Changes to your memory and thinking associated with ARBD are most likely to happen in:

- women who drink more than 50 units of alcohol a week for five years or more

- men who drink more than 60 units of alcohol a week for five years or more.

ARBD most often affects people in their 50s, but can occur at any age. Women who drink heavily tend to get problems with their memory and thinking earlier than men.

How does alcohol damage the brain?

Drinking a lot of alcohol for a long time causes several things that can lead to brain damage, including:

- Nerve cell damage – This leads to problems with memory and changes in behaviour.

- Vitamin deficiency – Alcohol makes it harder for your body to absorb vitamin B1 and other nutrients. Without enough vitamin B1 your brain cells can be damaged. If you drink a lot of alcohol, you might also forget to eat properly, which can cause further nutritional deficiencies.

- Blood supply to the brain – If you drink a lot of alcohol, you will have an increased risk of strokes, which can damage the blood supply to your brain.

- Head injuries – If you drink a lot of alcohol, you are more likely to experience head injuries. These can cause direct damage to your brain.

- Cerebella damage – This is the part of the brain responsible for balance and walking, and can become severely affected by alcohol use, and increase the risk of falls.

- Brain shrinkage – Our brains tend to get smaller, or shrink, as we age. However, research has shown that drinking a lot of alcohol can increase this shrinkage.

How can I tell if alcohol is damaging my brain?

If your brain is being damaged by alcohol, you might notice that you:

- become irritable

- have problems with attention, and get distracted by things around you or your own thoughts

- stop looking after yourself properly

- can’t remember whole periods of time or what you did

- lose your inhibitions and start to:

- say inappropriate things e.g. upset or threaten other people

- act physically, emotionally or sexually abusively towards other people.

These changes are caused by the effect alcohol has on the front of the brain, which controls behaviour and social interactions.

What types of ARBD are there?

There are different kinds of ARBD, including:

- Wernicke’s Encephalopathy

- Korsakoff’s Syndrome

- Alcohol-related dementia

Wernicke’s Encephalopathy happens when your body runs out of vitamin B1. If you have Wernicke’s Encephalopathy, one or more of the following three things might happen suddenly:

- you will become confused and disorientated, e.g not knowing where you are or what time it is

- you will become unsteady on your feet

- your eyes will move quickly from side to side (called ‘nystagmus’)

Of these three things, most people (80%) will only have signs of confusion.

Wernicke’s Encephalopathy is life-threatening, but can be treated if you get help quickly. The treatment for Wernicke’s Encephalopathy is an infusion of vitamin B1 injections. These will usually be given as a ‘drip’ in hospital, or as an injection at home.

If you or someone you know is showing signs of Wernicke’s Encephalopathy, call 999 immediately.

Wernicke’s Encephalopathy lasts for several days. Unfortunately, it can be missed or mistaken for being drunk. If left untreated, someone with Wernicke’s Encephalopathy can develop permanent memory problems. These are called Korsakoff’s Syndrome.

Korsakoff’s Syndrome happens when Wernicke’s Encephalopathy is left untreated. If you have developed Korsakoff’s Syndrome, you might show signs of brain damage, such as:

- personality changes

- being unable to remember anything that has happened recently. You might still be able to read, write and concentrate.

- difficulty learning new things

- losing memories of things that happened in the time before the illness started

- ‘confabulation’ – this is where you will try to fill in a gap in your memory with incorrect information. For example, by using an old memory in the wrong place. You won’t be aware that you are doing this, though other people might be.

Dementia is a general term for memory problems and changes in thinking and personality that get worse over time. Dementia is more common in older people.

Alcohol can cause dementia because it damages brain cells. Alcohol-related dementia creates problems with:

- memory

- problem solving

- personality changes.

Unlike with other forms of dementia, if you have alcohol-related dementia you won’t lose your language skills. However, this can make it harder for other people to notice that you have developed alcohol-related dementia. The symptoms of alcohol-related dementia can be mistaken for you being drunk. For example, if you seem to have less motivation, or are acting inappropriately.

Most types of dementia get worse over time. However, if someone with alcohol-related dementia stops drinking, their problems might stop getting worse, and even improve.

If you have mild ARBD, your memory and other thinking skills will often improve significantly after you have stopped drinking, though this can take some time.

If you have more severe ARBD, especially Korsakoff’s Syndrome, this might improve over two or three years after you stop drinking. However, some people will be left with severe problems and need long-term care.

For people with ARBD who stop drinking, it is estimated that:

- one in four will make a full recovery

- two in four will make some recovery, but be left with some problems

- one in four will continue to have severe problems.

The older someone is, the less likely they are to recover.

If you have ARBD and this affects your ability to function, you might be able to claim benefits or other forms of support. You can find out more about benefits, financial support and debt advice on our website.

If you are worried that you are drinking too much, and want help to stop drinking or to drink safely, speak to your GP. They should ask you:

- how much you drink

- how frequently you drink

- your history with alcohol

- if you have any other substance use disorders

- if you have any other mental or physical health problems.

This will help them to understand what kind of support you might need.

You can also refer yourself to a local alcohol service, without a GP referral. You can use the Frank website to find services near you.

Self help

Some people can reduce the amount they drink or stop drinking without professional help.

There are now some excellent online resources which can help you to work out what kind of support is best for you. Your GP should also be able to tell you about any local organisations or support groups that can support you to stop drinking or reduce how much you drink.

If you are dependent on alcohol and struggle to stop drinking on your own, you might be offered further support. For example, being referred to a community addiction service.

Psychological therapies

You might be offered a psychological therapy like:

- cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

- social behaviour and network therapy

- another behavioural therapy.

These will help you to understand why you drink, and how drinking affects your behaviour and social life.

Medications

Medically-assisted withdrawal

If you have more serious alcohol dependence, you might need help to stop drinking safely. Alcohol support services should assess you to work out whether you can stop drinking at home, or whether you should come into a specialist alcohol treatment centre.

Relapse Prevention Medication

Medications that can help you to avoid starting drinking again include:

- Acamprosate – This is a drug that can help to reduce the craving for alcohol. You can be given acamprosate once you have stopped drinking, and might take it for up to 6 months.

- Naltrexone – This is a drug that is used to stop the effects of alcohol to discourage people from drinking. You might take this for up to 6 months or longer.

- Disulfiram – This might be offered to you if you have tried taking acamprosate and naltrexone and these have not worked, or if you cannot take these other drugs for some reason.

Residential rehabilitation

You might be offered a place in a residential rehabilitation unit if you are also experiencing:

- physical health problems

- mental health problems

- social problems, such as with your housing or finances.

This should be for a maximum of three months. Whether you are offered residential rehabilitation will also depend on the availability of these services in your area.

Is it dangerous to stop drinking suddenly?

If drinking alcohol is affecting your physical or mental health, you might want to quickly reduce your drinking or stop drinking altogether. However, this can be very dangerous if you drink daily at high levels, or have been drinking for a long time.

Suddenly stopping drinking can cause you to:

- suffer from alcohol withdrawal symptoms

- experience epileptic fits – these will usually happen in the first 48 hours after you stop drinking. They usually happen after your withdrawal symptoms have already happened.

- develop the complications of severe alcohol withdrawal. E.g. DTs, Wernicke’s Encephalopathy or Korsakoff’s Syndrome.

It is important to slowly reduce your drinking. It is also safest to do this with help, especially if you have been drinking a lot for a long time.

Alcohol is addictive and can be difficult to give up. If you know someone who is dependent on alcohol and are trying to support them, consider the following steps:

- Find out more – Understanding what alcohol dependence is and how it works can help you to better understand the person you know and what you are both going through.

- Set your expectations – It’s common for someone to stop drinking for a long time, but then start again. While this can feel like a step back, remember that this doesn’t mean that they or you have ‘failed’. It also doesn’t mean that they won’t be able to stop again in the future.

- Understand what you can and can’t do – The person you know has to want to stop or reduce their drinking, and there is only so much you can do to help them to make that choice. It can be difficult if you know someone is hurting themselves or others with their drinking. Find someone who you can talk to about your feelings in confidence.

- Get support for yourself – If you know someone who is dependent on alcohol, your GP can put you in contact with local organizations that can help. Some organisations or groups are there to support families and friends specifically.

- Stay safe – If someone else’s drinking is putting you or someone you know in danger, speak to someone you trust. Call 999 if you are in immediate danger.

Information on alcohol

Alcohol advice, NHS – Information on alcohol, calculating units, calories and tips on cutting down.

Alcohol support services

Use the following websites to find alcohol support services where you live:

Alcohol Change UK – Alcohol Change UK is a leading UK alcohol charity, formed from the merger of Alcohol Concern and Alcohol Research UK. They offer information about alcohol and managing your drinking.

Information on alcohol dependence

- Alcohol-use disorders: diagnosis, assessment and management of harmful drinking (high-risk drinking) and alcohol dependence, NICE – This information from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence is written for the public so that people who are dependent on alcohol can understand what care they are entitled to.

- SMART Recovery – SMART Recovery is a charity that offers a national network of mutual-aid meetings and online training programmes to help people to abstain from addictive behaviours.

- Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) – AA is a self-help group that aims to support people with recovery from alcohol dependence. It offers meetings across the UK and abroad.

- With You – With You, formerly known as Addaction, is a charity that supports people with alcohol or substance use disorders. They offer information, services in England and Scotland, and an online support service.

Information for friends, family and carers

- Nacoa – Nacoa is a charity that provides information, advice and support for everyone affected by a parent’s drinking.

- Alcohol Change UK provides a list of support services for friends and family.

Information on ARBD

- ARBD Network – A network to raise awareness of alcohol related brain damage amongst healthcare professionals and the public through education and information.

- Alcohol-related brain damage: the road to recovery, Alcohol Change UK – A handbook for the families, carers and friends of people with alcohol-related brain damage (ARBD).

Domestic violence resources

If you or someone you know is experiencing domestic violence as a result of someone’s alcohol use, or if you think your drinking is leading you to take part in abusive behaviours, here are some useful resources:

- Domestic abuse: how to get help, Gov.uk – This website offers useful resources for people experiencing domestic violence across the UK.

- Respect Phoneline – Respect is a charity for people who think that they might be taking part in abusive behaviours and want to get help.

- Reporting child abuse, NSPCC – If you are concerned that a child is experiencing abuse or neglect, the NSPCC can provide you with advice.

Beer, cider and alcopops

Strength (ABV) | Half pint | Pint | Bottle/can (330ml) | Bottle/can (500ml) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Mild strength beer, lager or cider | 3-4% | 1 unit | 2 units | 1.5 units | 2 units |

Normal strength beer, lager or cider | 4-5% | 1.5 units | 3 units | 1.7 units | 2.5 units |

Extra strong beer, lager or cider | 7.5-9% | 2.5 units | 5 units | 3 units | 4.5 units |

Alcopops | 5% | - | - | 1.7 units | - |

Wine and spirits

Strength (ABV) | Single (25ml) | Double (50ml) | Small wine glass (125ml) | Large wine glass (250ml) | Bottle (750ml) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Wines | 12-14% | - | - | 1.5 to 1.8 units | 3 to 3.5 units | 9 to 10.5 units |

Fortified wines (sherry, martini, port) | 15-20% | - | 1 unit | - | - | 14 units |

Spirits (whisky, vodka, gin) | 40% | 1 unit | 2 units | - | - | 30 units |

Most of us underestimate the amount we drink. To check what is really happening, keep a diary of how much you drink over the course of a week.

This can give you a clearer idea of how much you are drinking. It can also help to highlight any risky situations – times, places and people that lead to you drinking more.

| Day | How much? | When? | Where? | Who with? | Units | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monday | ||||||

| Tuesday | ||||||

| Wednesday | ||||||

| Thursday | ||||||

| Friday | ||||||

| Saturday | ||||||

| Sunday | ||||||

| Total for week |

This information was produced by the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Public Engagement Editorial Board (PEEB). It reflects the best available evidence at the time of writing.

Expert authors: Dr Jim Bolton, Dr Tony Rao, Professor Wendy Burn and Professor Julia Sinclair

With special thanks to service user Ms Diane Goslar who helped to develop this resource.

Full references available on request.

Published: Feb 2024

Review due: Feb 2027

© Royal College of Psychiatrists