Obituaries

This page contains recent obituaries for College members (of all grades) and Honorary Fellows.

Obituaries from previous years are archived on our earlier obituaries page. The button below will let you find out how to submit an obituary.

2025

Written by Ursula Mackintosh (Olivia's sister).

Written by Ursula Mackintosh (Olivia's sister).

Olivia Guly, MB BS MRCPsych

Olivia, retired consultant in forensic psychiatry, based in Lancashire, died of breast cancer on 23 November 2025 aged 66.

Olivia was born in Hythe Hospital, in the New Forest in 1959. Aged 16, while a pupil at the Convent of the Sacred Heart, Woldingham, she wrote her first paper, published as a personal view in the BMJ, on her observations of her fellow boarders, who hid their anorexia nervosa from staff and other pupils. This made her unpopular with the headmistress, who feared it would put off prospective parents.

She qualified from St Mary’s in 1981. After House Officer posts in Windsor & Ascot, followed by an SHO post in Accident & Emergency in Taunton, she trained in psychiatry in Bristol and West Yorkshire, specialising in forensic psychiatry. Her research as a senior trainee was on single perpetrator, single victim child homicide.

In 1991, she started as the first consultant forensic psychiatrist in Lancashire and South Cumbria, at the Langdale Unit Interim Secure Unit. This post included prison sessions, and it was here, through her work, that she met her husband Phil, a prison officer. She was a trainer, which she enjoyed, but whereas for a while she had managerial responsibilities as Clinical Director, she always far preferred clinical work to management activities.

In 1999, by which time she had been joined by other consultant colleagues, she moved from the Langdale Unit to the newly opened Guild Lodge, which she had been instrumental in setting up. While there, she was involved in developing the forensic outreach service and long-term medium secure provision. She left Guild Lodge in 2001 to work in Norfolk, based at the Norvic clinic with responsibility for patients in the Great Yarmouth area, but in 2007 she returned to Lancashire and Guild Lodge, to be nearer to family. On her return to Lancashire, she worked predominantly in the women's service. Despite recognising how dangerous many of her patients were, she was passionate about ensuring they received the best possible care.

Although teetotal herself, she enthusiastically joined in work social events, often staying up well into the early hours with her colleagues and friends who were not.

She retired in 2014, but during Covid returned to work in the immunisation service in Preston. She commented how many of her immunisation clinic patients, unlike her detained patients, thanked her and the other staff for their care.

She enjoyed her retirement and was not tempted to return to psychiatry. She took great pleasure in making jam and cooking for friends and family, gardening, her many holidays in the Scilly Isles, and walking her rescue dogs.

She leaves her husband Phil, five stepchildren, step grandchildren, and great grandchildren, as well as three siblings.

Written by Professor Stephen Tyrer and Dr Christine Davison.

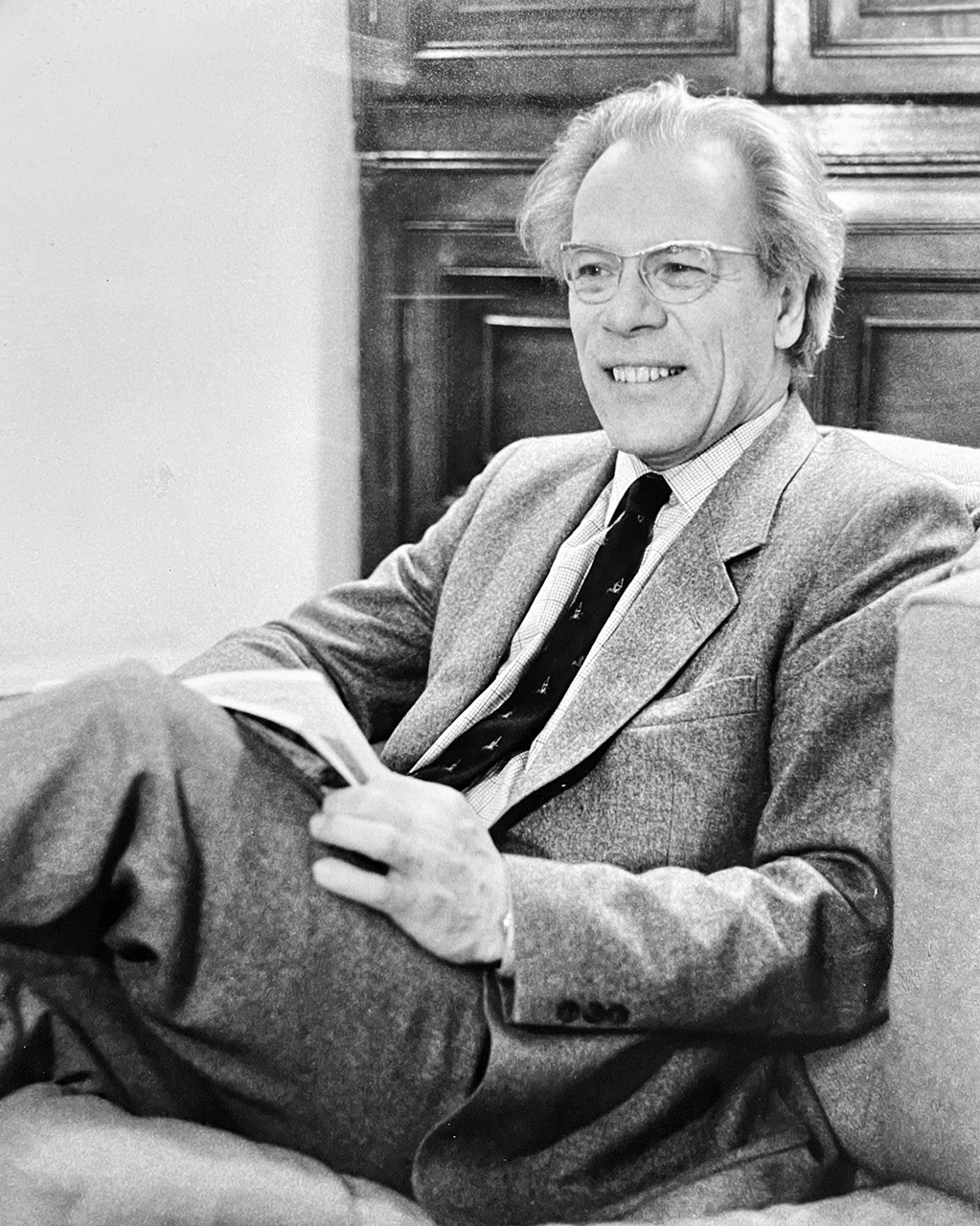

Dr Kenneth Davison FRCPsych FRCP (Edinburgh) FRCP (London)

Ken Davison, Emeritus Consultant Psychiatrist, died peacefully from old age on 5 August 2025, aged 96. He was the Director of NHS Services in Newcastle-upon-Tyne for over 30 years. Ken was the Gaskell Gold Medallist in 1964, considered the highest attainment in academic psychiatry. He was an expert in the field of psychiatric illnesses arising from neurological factors and he honed his expertise in this field following an attachment to the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery at Queen's Square in London.

Marrying his psychiatric skills with his neurological knowledge from Queen's Square, he examined the symptomatology of psychoses that resemble schizophrenia, but which were caused by underlying organic disorders of the brain, particularly cerebral tumours or epilepsy. This association of organic cerebral disorders with schizophrenia was much greater than one would expect according to chance and occurred in patients without genetic loading for schizophrenia. In particular, injuries to the temporal lobes and diencephalon were found to be strongly associated with the development of these illnesses. One review which Ken wrote on this subject is still widely quoted and has achieved almost 800 citations.

Ken Davison was a strong advocate for the Royal College of Psychiatrists. He was actively involved in the training and supervision of trainees, serving as the College’s Northern Regional Adviser as well as being Chair and Convenor of the Postgraduate Training Approval Panel for Scotland. He supported trainees throughout and, amongst others, he supervised Professor Femi Oyebode's MD thesis. His work for the College also included acting as an Examiner for the MRCPsych examination, being a member of Council from 1975 to 1980, and Chair of the North-East Division in the 1980s.

Having gained an international reputation that led him to be invited to several European Conferences and to advise on psychiatric services in Libya, Ken retired from his post as Consultant Psychiatrist and Director of the Department of Psychological Medicine at Newcastle General Hospital in 1989. At the ceremony commemorating his lifetime allegiance to the development of psychiatry in Newcastle, the then Dean of the Medical School explained that although everybody knew that Ken had always been a retiring man he had now achieved his ambition of retiring de facto. He remained, however, very active after retirement. He did medico-legal work, he was a team member of the Health Advisory Service, a member of the Mental Health Review Tribunal Panel, and a Second Opinion Appointed Doctor for the Mental Health Act Commission. He led the development of Audit in Psychiatry in Newcastle as Chair of the Medical Audit Committee for the Newcastle Mental Health Trust and Regional Lead Clinician for Medical Audit (Psychiatry). He was a long-standing member of a Continuing Professional Development group for local retired psychiatrists until his 90th Birthday.

Ken was born in Sunderland in 1929 to Thomas and Margaret. Growing up in humble circumstances, he was an only child but very close to his cousin, Derek Foster (later Baron Foster of Bishop Auckland, the Labour politician). He was educated at the Bede Grammar School in Sunderland at the same time as the renowned clinician in the field of pain, Harold Merskey, Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Western Ontario, Canada, who died last year. Harold has told us how he and Ken were always among the first three in their class. His school days were disrupted by the War, but he still obtained good results allowing him to achieve his ambition to train as a doctor, attending Newcastle Medical School (then part of the University of Durham) from 1947 to 1952. After house jobs at the Royal Victoria Infirmary, he did his National Service in the Royal Army Medical Corps and was posted to South Korea, Japan, and Hong Kong. Returning to civilian life, he worked in medicine obtaining his MRCP. He moved into psychiatry in 1958 where he trained under Martin Roth in Newcastle and Eliot Slater in London before returning to Newcastle to take up his consultant post in 1964.

Throughout his life, Ken enjoyed gardening, reading, classical music (he played the piano and trombone) and being in the wild landscapes of Northern England. Above all, however, Ken was a family man, married to his beloved Joyce for nearly 72 years – she predeceased him by only five weeks. He had four children of whom he was immensely proud, with his eldest daughter following him into a medical career. His latter days were marred by increasing physical frailty, but he retained his interest in all matters medical.

Ken Davison was the opposite of the driven go-ahead doctor who wishes to achieve fame and fortune. Despite his many achievements, he always kept his feet on the ground. He will be profoundly missed by his family, his colleagues and by the patients who were lucky enough to be under his care.

Obituary by Sheila the Baroness Hollins.

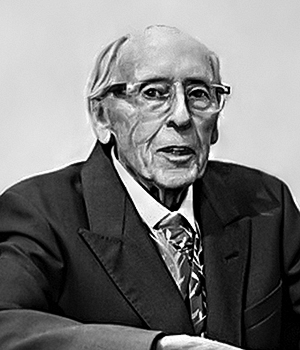

John Anderson Oliver Russell MA BM BCh DPM FRCPsych (18 January 1936–25 July 2025)

Oliver attended Merchant Taylors' School in London, studied human physiology at St John’s College, Oxford, and did his medical training at the Middlesex Hospital, London. His career spanned forty years as an NHS consultant psychiatrist, and a Reader in Mental Health at the University of Bristol, combining clinical practice and leadership with a strong applied research programme. He was a passionate advocate for closing long stay mental handicap hospitals where he had started his career in psychiatry. In 1976, Oliver was appointed to the Department of Health’s National Development Team, reporting on services for people with learning disabilities around the country.

At a local level he helped to transform services, giving people with learning disabilities the chance to live an ‘ordinary life’ in the community. The Wells Road Service was established in Bristol to assist in the resettlement of people from Farleigh Hospital, many of whom had been admitted as children at a time when mentally handicapped children were not entitled to education.

In 1988, Oliver co-founded the Norah Fry Research Centre in Bristol, which undertook an extensive and very practical research programme on services for people with a learning disability, including how to improve primary care and supported housing provision. He travelled widely, taking his expertise to Australia, Canada, Slovakia and the USA and sharing the best of what he had learnt abroad on his return home.

In 1998 his last major post was a 3-year secondment as Senior Policy Adviser in Mental Health to the Department of Health, a position that I took over in 2001. His major achievement in this role was to shepherd the development of the Valuing People White Paper. This was the first government policy co-produced by people with personal and family experience of learning disability. One of these self-advocates was Jackie Downer, who had been training medical students at St George’s with me, and accompanied me to an international Policy Academy arranged by the President’s Committee on Mental Retardation in Washington DC. Oliver met Jackie there and used the action plan that emerged from this event to inform the development of ‘Valuing People’. Jackie became his advisor when he was Chair of the Board of Trustees of the British Institute of Learning Disabilities and says of him that she “felt confident in this role because he always showed respect for me and listened carefully to my contributions”. Jackie gave a tribute at Oliver’s funeral.

Throughout his professional career including after his retirement, he was active in trying to improve the lives of people with learning disabilities through numerous voluntary organisations and professional advisory roles. Among these he was, at various times, an advisor to the government of Wales and its National Assembly, a trustee of Circles Network and later Honorary President, an advisor to the Foundation for People with Learning Disabilities and a Board member at the National Development Team.

Oliver was a ‘gentle giant’ in our field, always smiling, always optimistic despite facing many challenges. He was widely respected in the communities of people and families who really matter.

Oliver was a true friend to so many people and will be much missed. Especially of course by his wife for over 60 years, Rosemary, their three sons and eight grandchildren.

Written by David Gittleson, son of Dr Gittleson.

Dr Neville Leon Gittleson BM BCh MA DPM DM FRCPsych (20 May 1930 – 15 June 2025)

Dr Neville Gittleson passed away peacefully on 15 June 2025 at the age of 95, surrounded by his loving family. Born in Leeds in 1930, he was evacuated during the war to Ilkley before returning to Roundhay School, where he was a gifted student. Having gained a state scholarship, at the age of 16 he won an exhibition to read medicine at Balliol College, Oxford, going up in the aftermath of the war in 1947.

After graduating in 1953 with his BM and BCh, he spent two enjoyable years in general medicine as a house physician in Bangor and Llandudno before beginning his national service in the Royal Navy. As a medical officer attached to the Fleet Air Arm at HMS Daedalus in Lee-on-Solent, his duties included air sea rescue, testing new safety equipment and evaluating air crew. These proved to be formative years, for it was his naval experience that led to a strong desire to train in psychiatry. On completing his service in 1957, Neville moved to the Royal Infirmary in Manchester where he gained his DPM under the supervision of Professor Edward Anderson.

Neville then spent a year as a registrar at the Maudsley in the Professorial Unit of Aubrey Lewis, before accepting an appointment as a Senior Hospital Medical Officer at the Middlewood Hospital in Sheffield. He was rapidly promoted to consultant psychiatrist at the unusually young age of 33 and would remain in Sheffield for the rest of his career.

Sheffield provided a fertile and supportive environment in which Neville could pursue his interests in phenomenology, rehabilitation, teaching and forensic psychiatry. He published a wide range of papers, many building on his DM which was awarded by Oxford in 1965 for his research on obsessions and depression. Other areas of research included subjective ideas of sexual change, perception of the soul, tattoos in psychiatric patients and indecent exposure. He was forthright about building rehabilitation opportunities for institutionalised patients, becoming active in the Association of Occupational Therapists and publishing papers on advancements in this area.

Teaching was a lifelong passion. He was an Honorary Clinical Lecturer at Sheffield University and a generation of registrars benefited from his weekly teaching ward rounds. His influence was highlighted by one former student, now a professor, who wrote that Neville brought what he had learnt at the Maudsley to Sheffield, teaching him how to conduct a proper mental state examination. Neville’s teaching impact extended widely through courses run for medical students, nurses, general practitioners, midwives, social workers and newly appointed magistrates. He became an examiner for membership of the Royal College. Well into retirement, he would enjoy lecturing on the history of the Mental Health Act to a new generation of medical students.

Neville’s greatest interest came to be forensic psychiatry and he was regularly asked to be an expert witness in court cases. Reflecting some of his earlier research, he was invited to join the Policy Advisory Committee on Sexual Offenders for the Criminal Law Revision Committee’s 15th, 16th and 17th reports. He joined the Parole Board in 1978 and was a member of the Joint Home Office/Parole Board Life Sentence Committee, where colleagues regularly sought his advice. Neville was also an independent assessor for the Civil Service Commission’s prison department.

The latter stages of his career brought further variety. Neville worked both as a second opinion doctor for the Mental Health Act Commission and as a medical member of the Mental Health Review Tribunal for many years until he reached 70. He appreciated a very different role as part of the programme advisory council for Yorkshire Television.

His overarching priority throughout his career though was his family. Having met his wife Sandra shortly after moving to Sheffield, Neville was determined to be a husband and father first, even if that meant declining new roles and appointments. When very young, his two children David and Debbie had a limited understanding of what dad did as a psychiatrist. Going into infant school one morning, their announcement that dad was going to prison today caused some amusement amongst the teachers, who realised that Neville was visiting there in a professional capacity. Further glimpses into his work came with a two-part Man Alive TV series on Middlewood that aired in 1974 featuring Neville.

Neville was a very supportive, kind, modest and thoughtful individual, who was greatly liked, respected and trusted by colleagues and friends for his wise counsel and integrity. He was someone who cared passionately about helping people with mental health difficulties and ensuring their rights were respected, whatever their circumstances. Ahead of his time, he ran a mental health drop-in clinic at Devonshire Green in Sheffield for homeless people who felt unable to seek help through the hospital system.

Outside work, Neville would relax through his love of steam railways, photography, classical music and carpentry.

Neville is survived by Sandra, David and three grandchildren Matthew, Anna and Rachel. His daughter Debbie sadly predeceased him. Neville will always be remembered by his family as a truly inspirational, wonderful and kind man. His legacy is the set of values with which he lived his life and undertook his work as a consultant psychiatrist – have intellectual curiosity, treat all people with respect and courtesy, and act with integrity.

Submitted by Dr Malcolm Fraser, nephew of Marjory.

Dr Marjory Florence Foyle MB, BS, MD, FRCPsych

Dr Marjory Florence Foyle MB, BS, MD, FRCPsych

Dr Marjory Florence Foyle was a former Medical Missionary and International Itinerant Consultant Psychiatrist who died 9 April 2025 at age 103.

She spent the first part of her career practising as obstetrician/gynecologist in the Indian subcontinent and after developing depression, retrained as a psychiatrist and was director of a psychiatric hospital in Lucknow, India.

She retired in 1980 at age 59 and subsequently travelled to over 40 countries lecturing, training and counselling missionaries/NGO’s.

In 2006 , seven years after obtaining her MD from the University of London at age 78, Marjory was described by Dr Andrew Sims (former president of the Royal College of Psychiatrists) as being “one of the most influential psychiatrists in the world”.

Marjory's young life

Marjory was born 3 November 1921 at Milborn Port, Somerset and was the 3rd child of a marriage between a Methodist minister and a graduate mathematician.

She followed her older sister to the London Medical School for Women at the Royal Free Hospital.

Marjory studied medicine (the LMSW evacuated her to St Andrew’s and she proudly stated that she never touched a golf club) through wartime, receiving her final exam results in London on VE Day (she always had a knack of being in the right place at the right time).

Following junior doctor training at the Royal Free and Arlesey Hospitals, Bedfordshire (Former 3 Counties Lunatic Asylum - WW2 RF Emergency Hospital), she sailed to India in 1949.

Inspired by her committed Christian faith, Marjory worked for 15 years in hospitals in Lucknow, India and Tansen, Nepal as an obstetrician/gynaecologist to serve women whose culture prevented them consulting male doctors.

Entering psychiatry

After being appointed Clinical Director of a hospital in Lucknow, Marjory developed and received treatment for depression.

Recognising immense needs for psychiatric care in the developing world, in her forties she retrained in Psychiatry at Royal Liff Hospital, Dundee (effective 2001 merged into Ninewells Hospital).

Returning to India in 1968, Marjory became Director of Nur Manzil Psychiatric Centre, Lucknow. She was elected FRCPsych in 1980, and ‘retired’ in 1981.

Active in retirement

Post retirement a typical project that Marjory was involved in was the successful implementation (working with the United Mission to Nepal and based on a prior WHO funded project) of a Community Mental Health program in a poor rural area of Nepal which was subsequently written up in the World Mental Health Casebook (2002).

Marjory studied the psychological needs of missionaries, and pioneered the development of MemberCare (pastoral care and wellness program specifically designed for people working in demanding, high-stress mission/NGOs). She wrote Honourably Wounded (1997 – reprinted 4 times) on stress in cross-cultural mission/NGO workers, and also her autobiography Can it be me? (2006).

She travelled to over 40 countries in her retirement, lecturing and training and embraced technological developments such as computers, cell phones, email and the internet with zest.

She also provided psychiatric care to Missionaries with Interhealth (1989-2017) in London and was awarded an MD on Expatriate Mental Health (based on the work as described in Honourably Wounded) by the University of London at age 78 in 1999 – the oldest female to receive that degree.

From 1984 Marjory was pastorally supported by All Soul’s Church, Langham Place, London.

In 1985 Marjory and my mother spent Christmas/New Year with me (her nephew) and my family in St Petersburg, FL. At the time the Royal Navy routinely sent a Frigate on a tour of duty around the Caribbean which ended in St Petersburg for Christmas. As a UK trained physician, I acted as an informal contact between the ship’s doctor and the local medical community.

Early on Christmas morning 1985 I received a phone call from the Ship’s doctor saying that a Gurkha soldier had inexplicably attacked one of the ship’s officers. Did I happen to know of a western trained Psychiatrist who spoke Nepali? At the time there were two in the world of whom Marjory was one. I drove her and my mother (who was determined not to be outshone by her younger sister and miss out) to the harbour. Marjory sorted out the situation, no charges were filed against the Gurkha and we were subsequently treated to very generous hospitality in the Wardroom. As previously stated, Marjory had a knack of being in the right place at the right time

A wonderful sense of fun

Marjory had a beaming smile, a wonderful sense of fun and a mischievous sense of humour, with inspiring wisdom, humility and compassion. She walked the London Marathon course annually into her nineties and enjoyed frequent Birdwatching visits to the WWT London Wetland Center at Barnes.

She died peacefully 8 April 2025 at David’s House, Harrow, London.

Marjory leaves her nephew Malcolm Fraser and two great nieces (all doctors in USA), and her wider family and friends in London and around the world.

Submitted by Dr Bruce Scheepers, friend and colleague.

Submitted by Dr Bruce Scheepers, friend and colleague.

Dr Stewart Vaggers died peacefully on 13 July 2025 at the age of 65. He was a Consultant Forensic Psychiatrist, Medical Director, legal scholar, and Fellow of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, remembered for his integrity, intellectual curiosity, and deep commitment to both psychiatry and the law.

After beginning his academic life in psychology, Stewart qualified in medicine and obtained Membership of the Royal College of Psychiatrists in 1990. Shortly thereafter, he pursued a long-standing interest in the law, completing an LLM and working briefly at a prestigious law firm. However, his passion for psychiatry drew him back, and he completed specialist training in forensic psychiatry.

In 2000, Stewart was appointed Consultant Forensic Psychiatrist with the South Staffordshire and Shropshire NHS Foundation Trust, later serving as Medical Director from 2003 to 2007. He became a Fellow of the College in 2013. Known for his calm leadership, clinical insight, and ethical clarity, he contributed significantly to the development of forensic services in the region. His rare combination of psychiatric and legal training made him particularly effective in navigating complex medico-legal issues and promoting patient-centred care within secure environments.

During his consultant career, Stewart developed inclusion body myositis, a progressive muscle-wasting condition that eventually led to his early retirement from clinical practice in 2014. Despite this, he continued to serve the field as a Medical Member of the Mental Health Tribunal and undertook expert witness work in the private sector for several years. His resilience, professionalism, and sense of purpose remained undiminished.

Beyond his professional life, Stewart was a devoted husband and father, a private and principled man who cherished his family. He had a lifelong love of modern art, theatre, and Liverpool Football Club, and he bore serious illness with courage, humour, and grace. Even after being diagnosed with a glioblastoma brain tumour, he exceeded expectations and milestones—walking his daughter down the aisle, becoming a grandfather, and celebrating Liverpool’s 20th league title.

Dr Vaggers is survived by his wife Sue, his children Sophie, Emma, and Max, and his grandson Joshua. He leaves behind a legacy of compassion, intellectual breadth, and quiet strength—an example to colleagues and trainees alike.

Written by Jeremy and Gregory Bell, sons of Dr Bell.

Dr David Samuel Bell FRANZCP, FRCPsych

It is with great sadness that we announce the peaceful passing of Dr David Samuel Bell FRANZCP, FRCPSYCH, on 2 April 2025 in Sydney, Australia, at the age of 94.

Born in Sydney during the Great Depression on 20 February 1931 to Max and Betty Bell, David is survived by his beloved wife of 68 years, Judy; his children, Gregory, Jacqueline, and Jeremy; seven grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.

Even as a child, David’s vocational clarity was remarkable. When asked what he wanted to be, he confidently answered ‘a psychiatrist’ – a word neither he nor his teacher could spell. It was a prescient moment that foreshadowed a lifetime of inquiry into the human mind.

David’s career spanned more than 55 years. He was a prolific author, academic, WHO Fellow, department head, VMO at St Vincent’s Hospital, private practitioner, group therapist, and pioneering medico-legal expert. He was also a skilled photographer and passionate gardener, pursuits that balanced the intellectual rigours of his profession.

He consistently challenged prevailing psychiatric orthodoxy in pursuit of better mental health care and justice. His contributions to drug addiction treatment, epilepsy care, and community psychiatry were significant. His time at Callan Park was particularly formative, exposing him to both the best and worst in psychiatric care – including the controversial practices of Dr Harry Bailey. This experience deeply influenced his lifelong commitment to compassionate, evidence-based treatment.

Throughout his life, David was captivated by the fundamental mystery of how thought arises from matter. In later years, he mused on the parallels between human cognition and the emergent behaviours of artificial intelligence – a subject he approached with characteristic curiosity and scepticism.

One of his major medico-legal contributions occurred in the 1980s, when MRI technology was first introduced in Australia. Recognizing its forensic value, David pioneered the use of MRI scans to identify trauma-induced brain changes. He created simplified diagrams from MRI data to help legal professionals grasp complex neurological evidence – enabling more accurate adjudication in cases involving behavioural change following head injuries. His work allowed many clients to receive fair compensation where otherwise their injuries may have been dismissed or misunderstood.

David’s critiques were never cynical; they stemmed from a sincere desire to strengthen psychiatry through scientific rigour. He believed in confronting root causes, not merely treating symptoms. His emphasis on the ‘group mind’ – how collective thinking can reinforce error – underpinned his work in both psychiatry and forensic science.

Despite a demanding career, his family remained at the centre of his life. Growing up in the 1960s, his children recall the grounds of Callan Park as their playground – a reflection of his dual devotion to family and profession. They also remember seeing the ECT treatment rooms and watching their father on national television, introduced as ‘the drug addiction expert’.

To his family, David was never defined by his professional titles. He was a loving husband and father first. Yet, when asked what he did for a living, they were proud to say: ‘He’s a psychiatrist’ – often met with a joking reply about ‘shrinks’ and couches, though in truth he rarely used either.

David published extensively in journals such asThe Lancet,Brain,British Journal of Psychiatry,American Journal of Psychiatry,Medical Practice,Australian Journal on Drug Dependence(which he also edited), and theAMA Gazette. His medico-legal expertise, particularly in head injury assessment, was widely sought after, and he became a leading expert witness in high-profile cases – always with integrity, never with fanfare.

David was a life member of the Australian Academy of Forensic Sciences, and made enduring and substantial contributions to the Academy.

In his later years, slowed by illness but still mentally agile, he retained his love of the difficult question. Had we been able to speak with him one more time about consciousness, AI, or the ethics of psychiatric diagnosis, no doubt he would have leaned forward, raised a brow, and said, ‘Yes, but what’s the evidence?’

The field has lost a critic, a mentor, and an architect of rigorous thought. Those of us who had the privilege to work alongside David know we have also lost something more: a man who reminded us that psychiatry, law, and science are not just professions, but moral undertakings.

He leaves a legacy of intellectual honesty, curiosity, and fearless inquiry. His personal values – truth, kindness, tolerance, and resilience – guided his family as much as his professional life. He was a man unafraid to challenge the status quo when it meant advancing understanding or advocating for justice.

David Bell’s life embodied the highest ideals of medicine and science. His contributions to psychiatry, forensic science, and public understanding of mental health will resonate long beyond his lifetime. His legacy lives on through the countless people he influenced, the knowledge he generated, and the compassion with which he approached all aspects of life.

Those wishing to explore David’s body of work – including his autobiographical reflections inWelcome to the Loony Bin: 55 Years Inside Psychiatry and the Law– may visitBrainaction, where a comprehensive bibliography is also available.

Bell, J., & Bell, G. (2025). Dr David Samuel Bell FRANZCP, FRCPSYCH, 20 February 1931 – 2 April 2025.Australian Journal of Forensic Sciences, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/00450618.2025.2510059

Written by Dr Sebastian Kraemer.

Dr Mary Lindsay MB FRCP FRCPsych FRCPCH(Hon)

Dr Mary Lindsay MB FRCP FRCPsych FRCPCH(Hon)

Mary Lindsay qualified in medicine in 1951 and, as Dermod MacCarthy’s paediatric registrar, appeared in James Robertson’s influential film ‘Going to hospital with mother’. Later, as a consultant child psychiatrist, she worked again with Dr MacCarthy and his patients, pioneering the model of liaison work described in ‘I sit in the Diabetic Clinic’.

In 1976, Dr Lindsay was elected to the British Paediatric Association, and in 1993 elected FRCP, a rare honour. In 1974, she and Dr MacCarthy started the celebrated child psychiatry/ paediatric meetings at the postgraduate centre at Stoke Mandeville Hospital, which took place three times a year and continued for 18 years. In 2022, Mary’s devoted tribute to her mentor, the first British paediatrician to admit parents to a paediatric ward, was published in the Archives of Disease in Childhood.

Mary Lindsay was a distinguished presence at the interface of paediatrics and psychiatry for six decades, with many lectures and publications to her name, from 1955 to the 2023. In an early paper following up children with coeliac disease, she noted how chronic disease slows the child’s development. From her medical beginnings as a junior paediatrician, she championed the right of children in hospital to have their parents visit and stay the night with them. Her final paper was a huge and brilliant study, including some personal reflections, of the changing history of parents’ access to their hospitalised children over three centuries. Sick Children and their Parents is published online by the British Society for the History of Paediatrics and Child Health.

Obituary provided by Mr Robert Bownes, his son.

Dr Ian Thomas Bownes MD MRCPsych (6 January 1956 - 7 January 2025)

Dr Ian Bownes was an award winning pioneer of psychiatry in Northern Ireland during and after the Troubles. In 1991 he became only the second qualified consultant forensic psychiatrist in Northern Ireland and one of the first from the region to be added to the Royal College of Psychiatrists' Roll of Honour after receiving both the Peter Scott Memorial Fellowship and the John Dunne Medal for excellence and originality in psychiatric research.

Dr Bownes began his medical career after graduating from Queen’s University Belfast in 1978. Following a spell working in A&E as a junior doctor during the most violent period of the Troubles, Dr Bownes chose to embark on a career in psychiatry. One of his first assignments as a trainee psychiatrist was to assess whether paramilitary inmates housed at the notorious H-blocks of the Maze prison were mentally fit to go on hunger strike. This was both a testament to Dr Bownes’ bravery and a startling example of how underserved psychiatric services were in Northern Ireland at the time.

Spurred by this experience, Dr Bownes chose to dedicate his career to developing psychiatric services and treatments for prisoners. To that end, he took every opportunity to develop his expertise, including collaborating with Professor Gísli Guðjónsson, a professor of forensic psychology at King's College University of London, on three research articles on the attribution of blame for criminal offences and reasons why suspects confess during custodial interrogation.

By the early 2000s, Dr Bownes had become the senior psychiatrist at a number of major prisons, where he continued to campaign for change while building a thriving medical legal practice. His work included providing testimony to the Stormont Assembly and Parliamentary Select Committees on the inadequacy of Northern Ireland’s psychiatric resources, chairing the Forensic Faculty of the Northern Ireland Division of the Royal College of Psychiatry from 2010 to 2014 as it helped to shape mental health and capacity legislation, and worked to develop Northern Ireland’s Personality Disorder Strategy (2010).

As one of the UK’s most experienced forensic psychiatrists, Dr Bownes provided expert testimony on hundreds of criminal cases, including some of the country’s most serious and high profile offenders. His expertise was also sought by the UK security services on issues such as IRA informant Stakeknife.

Despite the often harrowing nature of his work, Dr Bownes stayed true to his ideals that everyone deserves the best possible psychiatric treatment and that with the right support and early intervention, offending could be prevented. He retired in 2023 after more than 40 years of service.

Outside his medical work, Dr Bownes was a prolific collector of antiques and curios, a skilled DIY practitioner and a dedicated family man. With his wife Sharon, who he met at university, he raised six children – Gareth, Philip, David, Felicity, Amy and Robert – several dogs, an inordinate number of rabbits and a handful of guinea pigs. His family will remember him for his eccentric sense of humour, imagination, impressive mustache and tireless work ethic.

2024

Obituary provided by Emad Salib, colleague and friend.

Dr Bertram Keir Brooker, Former Consultant Psychiatrist at Halton Hospital, North Cheshire

Dr Bertram Keir Brooker (“Bert”) passed away peacefully on December 19, 2024, at the age of 92, surrounded by the love of his family. Predeceased by his beloved wife of 61 years, Berra, just three months earlier, Bert’s final chapter was marked by quiet courage as he faced dementia in his later years, buoyed always by the legacy of a remarkable life well lived.

Born and raised in Wallasey in 1932, Bert’s early years were shaped by the upheaval of World War II, including being evacuated to Wales during the Blitz. These formative experiences instilled in him a lifelong resilience and an innate ability to adapt to life’s challenges – a theme that would echo throughout his storied career and personal life.

A dedicated student with an early passion for medicine, Bert graduated from Liverpool University in 1955, earning his MB., ChB., and later achieving his DPM and MRCPsych. His career was as varied as it was distinguished. From house jobs at Clatterbridge to life-changing service in the Royal Air Force, Bert’s journey spanned continents and disciplines. His time in the Hebrides, St. Kilda, and Antarctica – where he served with ingenuity and compassion – earned him the Polar Medal, a testament to his adventurous spirit and skill under extreme conditions.

After leaving the RAF and holding various hospital and GP posts in the Wirral and Liverpool in the early 1960s, Bert chose psychiatry as his lifelong career. In 1964, he accepted a registrar post at the Royal Liverpool Infirmary, which evolved into a lecturer role and eventually a research fellowship at Liverpool University.

In 1962, Bert married Berra, the love of his life. Together, they built a home filled with warmth, laughter, and a shared commitment to family and community. They raised four children, who followed diverse and successful paths, and were blessed with nine cherished grandchildren.

Bert’s professional life blossomed when he became a consultant psychiatrist in Warrington to serve Halton district in 1973. Over 27 years, he poured his energy into building highly regarded psychiatric services in Halton from the ground up, ensuring that those in need received compassionate, patient-centred care. His commitment to his patients and colleagues was reflected in the many leadership roles he assumed and the naming of a new psychiatric unit 'The Brooker Centre' in his honour – a rare and well-deserved accolade.

Despite his demanding career, Bert made time for his many passions: mountaineering, cricket, bridge, skiing, golf, and his enduring love of theatre, opera, and fixing things. These pursuits reflected his curiosity, determination, and zest for life. In retirement, Bert continued to inspire those around him with his wit, wisdom, and generosity of spirit. Even as dementia clouded his later years, his essence – a man of intellect, humour, and compassion – remained a guiding light to his family and friends. Bert’s legacy is one of service, kindness, and a life lived to its fullest.

He leaves behind his four children – two consultant anaesthetists, physiotherapist, and an artist – nine grandchildren, and countless others whose lives he touched. I, for one, feel most fortunate and privileged to have had this great man in my life for 47 years as a highly regarded colleague, mentor, and a very dear friend. A born adventurer, Bert aptly referred to death as 'the last great adventure'. Rest in peace, Bert, reunited now with Berra. Together, you leave behind a legacy of love, adventure, and an enduring reminder of what it means to live with purpose.

Dr Fenwick died at his home in London on 22 November 2024, aged 89 years.

You can read an obituary about his life and work on the Telegraph's website (free registration required).

Obituary by Victoria Aseervatham, daughter of Dr Van der Knaap.

.jpg?sfvrsn=a76d3d84_3) Dr Jill Van der Knaap (née Close)

Dr Jill Van der Knaap (née Close)

Jill Van der Knaap was born in 1943. Despite coming from a family with no medical background, modest means and negligible influence, she made it to the London Hospital Medical College to train as a doctor and qualified in 1967. The London's motto was “Nothing of man is foreign to me” and Jill shared that too with a never ending interest in understanding people and an unerring instinct to help the underdog. She became a psychiatrist, initially working at St Mary's and the Tavistock with children.

Later in life she worked with people with learning disabilities and she believed society is enriched by valuing people with learning disabilities, working to end the isolation, burden and stigma that could occur. She is remembered for being utterly reliable. She emphasised paying attention to supporting systems, the importance of attachment, relationships, communication and connection and bearing witness to peoples stories and being the person you could say the unspeakable to and be understood. Her last role was as consultant in learning disabilities in Hertfordshire.

After retiring she was a keen organiser and attender of reunions and arranged the Harperbury Hospital Old Girls (HOGs) meet ups and attended the LHMC events. She died on 10 Dec 2024 aged 81 of bronchopneumonia, after a very happy year living in a care home where she was the ‘poster girl’ of care home life, living life to the full.

Obituary by Mrs Heather Moriarty-Phillips, wife of Dr Phillips.

Dr John Ernest Phillips MB BCh DPM FRCPsych MRCPsych (Canada)

Dr John Phillips, born in 1935 in Barry South Wales to parents Evelyn and Ernest, died in October 2024 aged 89 of heart failure following a heart attack some twelve months earlier.

Dr John Phillips, born in 1935 in Barry South Wales to parents Evelyn and Ernest, died in October 2024 aged 89 of heart failure following a heart attack some twelve months earlier.

He had lived his retirement in Norfolk where he was rejuvenated by the countryside which he enjoyed exploring with his wife Heather, his young children and various lively dogs. He was passionate about his hobbies of photography, golf and keeping fit and maintained an interest in all sports.

John qualified as a doctor in 1960 at the University of Wales, Cardiff and embarked on psychiatry as his chosen path at Fulbourn Hospital Cambridge before deciding to work abroad in Canada. There he worked as a government psychiatrist in Victoria British Columbia then took a post as a teaching fellow for the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

In 1970 back in the UK he was appointed consultant psychiatrist for Torbay Health authority in Devon. He always said the most stimulating time of his career was to be instrumental in the planning of a purpose built 60 bed psychiatric unit on the site of the district general hospital, thus providing the start of care in the community in the Torbay area and the closure of the mental hospitals that served it.

He took a special interest in the development of alternative methods of care for the young chronic behaviorally challenging schizophrenics. He moved from local management duties on to regional medical committees, a secondment to the Health Advisory Service to assess psychiatric services and was also appointed as a second opinion doctor to the Mental Health Act Commission. He served as a member of the executive council of the South West division of the Royal College of Psychiatrists and was subsequently elected to the Fellowship of the College.

John married his second wife Heather and they adopted two babies in Sri Lanka when John was aged 55 and he threw himself into being a very active father. He retired in 1993. His initial retirement was short lived returning to work with the NHS for five years for a learning disabled facility, then assisted in the start up of an eating disorder clinic and spent a few more years in forensic psychiatry.

Eventually he was persuaded into full retirement on the cusp of reaching 70. He was able to spend a lot of time with his two adopted children, Joanna and James. Following his heart attack and the resultant heart failure he had two goals, one was to see James’ daughter born, and the other to be able to walk Joanna down the aisle at her wedding and make the father of the bride speech. He achieved both thankfully.

His energy, love and laughter showed through to the end and he is sorely missed, a much loved husband, father and grandfather. He is survived by his wife Heather, Joanna and James, his younger brother Barry and his sons Mark and Adam from his previous marriage.

Obituary by Gemma Mulreany and Sam Corner, RCPsych staff.

.jpg?sfvrsn=8cb67813_3)

Photo courtesy of Alicia Canter

Professor Sir David Goldberg was a groundbreaking figure in modern psychiatry whose work helped transform mental health services globally. A proponent of integrating mental healthcare into primary care, his career saw him publish distinguished epidemiological research, develop influential tools and frameworks, and train and mentor countless psychiatrists and other health professionals. In addition to his sharp intellect, he was known for his humility, warmth and wit.

Born in 1934 in Hampstead Heath, north London, David entered a world on the brink of upheaval, with the Second World War looming. He was raised with his brother and sister by parents Paul Goldberg and Ruby (née Brandes), descendants of Jewish immigrants from Germany. After the war broke out, the family took in a cousin who escaped Nazi Germany via the Kindertransport.

In 1943, Ruby and the children were evacuated to Oxfordshire. Although distanced from the direct conflict, the family often faced prejudice, and many locals treated them as outsiders. David began to question why people he had never met – whether from Oxfordshire or Germany – would wish him harm. These early experiences may have contributed to his curiosity about human behaviour.

David developed a keen interest in his father’s post-war work as a civil servant managing government training centres and rehabilitation units for returning soldiers. Psychologists would visit his father at the family home, and David often listened in to their work discussions around the dinner table.

At school, he listed psychiatry and biophysics as his top career choices, long before he knew much about either. Inspired by Oliver Zangwill’s An Introduction to Modern Psychology, he decided to pursue psychology. However, his father only agreed on the condition that he study medicine as well. As his father was the one paying, David conceded. It was a decision he didn’t regret.

David began his university studies at Hertford College, Oxford, in 1952, before completing clinical training at St Thomas’ Hospital in London. Specialising in psychiatry at the Maudsley starting in 1963, David trained under prominent figures such as Professor Aubrey Lewis – whose presence at the institution drew him to train there – and Professor Michael Shepherd.

David published two widely adopted research tools that have advanced the ability to assess mental health in diverse contexts – the Clinical Interview Schedule in 1970, and the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) in 1972.

Widely used in low- and middle-income countries, a tailored version of the GHQ has allowed practitioners to screen for mental health conditions without requiring specialist training, bringing care to underserved communities. At the University of Manchester, where he became a senior lecturer in 1969 and professor in 1972, David was responsible for teaching around 300 medical students and around 50 junior psychiatrists each year.

All the while, his interest in primary care psychiatry was a developing theme, and after a year as a visiting professor in the States, he was fuelled by more observations of mental disorders being missed in primary care. His research on this topic continued upon his return to Manchester in the form of a collaboration with colleague Professor Peter Huxley. In 1980, the pair developed the Goldberg–Huxley model, also known as the filter model, which outlined the stages of the pathway to psychiatric care, highlighting that the majority of mental healthcare takes place in primary care settings rather than specialist environments.

This work influenced mental health policy, underscoring the need for GPs to be equipped to manage psychiatric disorders. David introduced weekly GP training sessions, focusing on practical diagnostic skills and interview techniques.

Reflecting on this, Professor Dinesh Bhugra, a former RCPsych President and close personal friend, says:

“David was an extraordinary thinker who recognised the importance of primary care psychiatry early on and brought it into focus. His work bridged mental and physical health, changing how we view patient care.”

His influence also extended globally. As a long-term consultant to the World Health Organization, a role he continued into retirement, he contributed to revisions of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), ensuring its frameworks reflected cultural differences. Professor Bhugra adds:

“He frequently travelled to give talks and share knowledge, which was deeply important to him.”

He also created a master’s programme aimed at international trainees wanting to study in the UK. Often, he went above and beyond, helping them find accommodation and navigate practical challenges like opening bank accounts. Through his teachings and research, David explored the social determinants of mental health. He recognised that poverty, education, and social conditions profoundly shaped psychological wellbeing, and he advocated for holistic approaches that considered patients’ lives beyond their symptoms.

In the UK, mental healthcare was increasingly delivered in the community, due in part to the Mental Health Act 1959. David encouraged students to consider how services in their countries could improve, and many later influenced policies in nations like India and Pakistan.

Among like-minded others, David played a role in advocating for psychiatric training standards to be raised. During the 1960s, as plans were under way for the Royal Medico-Psychological Association to transition into the Royal College of Psychiatrists, a group of trainees vehemently opposed proposals for a stand-alone membership examination. They were adamant that the plans for the new College should instead prioritise ensuring high standards of specialist training across all locations under its remit, with the exam secondary to that. David supported the trainees, facilitating a letter to The Guardian, which amplified their shared concerns. The trainees’ advocacy efforts contributed to reforms that made training and standard-setting central to the new College, something that continues to this day.

David’s written works are another important element of his legacy. Among the books he authored and co-authored, the seminal The Detection of Psychiatric Illness by Questionnaire, remains foundational to psychiatric research and practice. This is all in addition to his research papers, of which he published over 300.

In recognition of his services to medicine, David was knighted in 1997, and, in 2009, he received RCPsych’s first-ever Lifetime Achievement Award, honouring a career dedicated to alleviating suffering and advancing mental health services. The David Goldberg Centre, part of King’s College London, was established in his name after his retirement in 2000 and continues his work by advancing research and training future generations of psychiatrists.

Despite the extent of his accomplishments, David remained unpretentious and humble. In his homelife, he shared over five decades of marriage with Ilfra (née Pink), a distinguished gastroenterologist. David credited all his professional achievements to her, who he described as his 'basis of stability and happiness'. Married in 1966, they raised four children – Paul, Charlotte, Kate, and Emma – and were together until Ilfra’s death in 2017.

David passed away in September aged 90, having developed Alzheimer’s a few years earlier. In tribute to him, his Oxford college, Hertford, flew its flag at half-mast during the week of his passing.

His children remember him as a resourceful and loving father with a 'wartime mentality' who viewed challenges as surmountable. His daughter Kate recalls how he preferred to build furniture rather than buy it, and how he engaged in debates about literature that inspired her to become an English teacher. She says:

“He was kind, generous, and always reading.”

Professor Sir David Goldberg once said he didn’t want to be remembered, but his impact on psychiatry – marked by compassion and innovation – continues to influence patients, colleagues, and trainees worldwide. In addition to his four children, he is addition to his four children, he is survived by nine grandchildren.

Obituary by Indrajit Tiwari, close friend of Dr Karki, and Akash Karki, Dr Karki's son.

.jpg?sfvrsn=309e6a3c_3) Dr Chuda Bahadur Karki MRCPsych FRCPsych (7 November 1948–28 August 2024)

Dr Chuda Bahadur Karki MRCPsych FRCPsych (7 November 1948–28 August 2024)

Dr Chuda Bahadur Karki, retired Consultant Psychiatrist and Clinical Director, Northeast Essex PCT, died from heart failure following cardiac surgery aged 75.

Chuda was born in Bhojpur, Nepal, in the foothills of the Himalayas and was the eldest of 9 siblings. He was the first in his family to attend university. As there was no local school, his education only started aged eight, when his grandfather sent him to Kathmandu. He quickly caught up as his headteacher promoted him to the next class every six months. He first studied botany at University before graduating from MLN Medical College, Allahabad, India in 1972.

He returned to Nepal to work at health centres in remote areas before he came to the UK in 1979. Here, he initially worked in Scotland before training in England where he developed his special interest in learning disabilities. He was appointed as a consultant at New Possibilities Trust in 1989. Chuda pursued psychiatry and applied the same vigour here to succeed. He did, retiring as medical director of the Trust. Probably the first one from Nepal.

Chuda was a long serving Fellow of the Royal College of Psychiatrists and also a member of its Diaspora group. The College also supported Chuda by providing educational materials for his post-earthquake relief work in Nepal, following the disaster in 2015. Here he helped to train over 50 Nepalese psychiatrists and psychologists in EMDR to help people suffering from post-traumatic stress symptoms.

Dr Karki will be remembered for his kindness, dedication and the positive impact he had on patients with learning disabilities. He was actively involved in service development. His inclusive, holistic approach helped advance the care of his patients and challenge societal norms. As head of R&D at New Possibilities Trust he was committed to regular audits, emphasising lessons learnt to drive forward positive change and nurture the next generation of psychiatrists. He was honoured with a BAMM Fellow Award for leadership during his directorship tenure.

Chuda was one of life’s good guys. Giving back was a fundamental guiding principle. He was a founding member of the Nepalese Doctors Association UK and past Chair. A deeply engaged Rotarian, who was also involved with various charitable organisations locally and abroad. He joined medical camps in Sierra Leone, Russia, India, and Nepal to support people not fortunate enough to get adequate medical care.

He was a passionate gardener and traveller who always wanted to take part in another adventure, to explore and help the world that little bit more.

Dr Karki is survived by his wife, Anju and two sons, Abhi and Akash.

Obituary by Dr Alistair Macleod, son of Dr Macleod.

Dr Torquil Hector Rees Macleod MB BS FRCPsych DPM, born 5 April 1930, died 10 April 2024

Dr Torquil Hector Rees Macleod MB BS FRCPsych DPM, born 5 April 1930, died 10 April 2024

Dr Torquil Macleod, who has died aged 94, was a retired consultant psychiatrist and Fellow of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. He was born in Winnipeg, Canada, in 1930, the first son of Hebridean parents. His father was an army Major and his mother was a medical doctor. In 1938, the family returned to Britain and soon after Torquil and his brother were evacuated to the Isle of Lewis, for the duration of the Second World War. After the war, Torquil moved to Edinburgh, where he attended George Heriot’s school

Torquil was directed to follow in his mother’s footsteps and studied medicine at Charing Cross Medical School, qualifying in 1955. He developed his passion for classical music, in particular chamber music and became increasingly interested in Hi-Fi. Soon after qualifying, Torquil was conscripted into National Service, first as a Captain in the Royal Army Medical Corps in Cairnryan, Scotland, followed by an eighteen month tour of duty in Ghana. Despite the challenges of working in a developing country, Torquil enjoyed his time in Ghana immensely.

Back home in Britain, Torquil returned to Charing Cross to train as a psychiatrist, attaining the Diploma of Psychological Medicine in 1962. It was during this period that he met Ann, who was working as a staff nurse at Charing Cross Hospital. They married in Hampstead in 1963 and last year they celebrated their sixtieth wedding anniversary, after a long and happy marriage.

Eventually, Torquil’s career took him to Liverpool, where he became a lecturer at Liverpool University, honorary senior registrar and then consultant in adult general psychiatry at Rainhill Hospital, which at the time was one of the largest psychiatric hospitals in Europe. It was in Liverpool that Torquil and Ann’s three sons Alistair, Duncan and Calum were born.

By the mid-seventies, Torquil was ready for another change and he felt the pull to return to the Hebrides. He took a job as a single-handed GP on the east coast of Lewis, where the family lived in a small, remote village. Torquil continued to work in General Practice for a few years, having moved to the other end of the country, in Poole, Dorset. However, he missed psychiatry and he made the unusual step of ‘breaking back’ into the specialty, securing a consultant job at Sutton Hospital in south London. Here he received medical students from St George’s Hospital medical school, undergoing their rotation in psychiatry.

Torquil was passionate about teaching and felt privileged to have been involved in the training of many junior doctors and medical students over the years. Torquil loved this stage in his career, developing the wards and raising the morale of the team. This led to his unit winning a ‘Centre of Excellence’ award, one of only four in the country, at the time. Liaison work with the College, led to Torquil being elected to Fellowship of the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

Retirement came in the early nineties and a move back to the south coast, this time to Seaford, in Sussex. Torquil took up the viola and it wasn’t long before he formed a string quartet, that met weekly for the best part of twenty years. Torquil also studied for a certificate in Music Composition at Sussex University and went on to compose two string quartets.

The pandemic brought an end to the quartet meetings, but Torquil kept in touch with his friends and family with weekly blogs, that were filled with anecdotes, jokes and aphorisms and he continued the blogs up until the time of his death. His love of loudspeakers never left him and at the age of ninety-three he could still be found in the garage, with a saw and drill, making one of his patented loudspeaker cabinets.

Torquil enjoyed good health throughout his life, until the last few months. He died peacefully at home, surrounded by his family.

Obituary by Dr Sasi Mahapatra, friend of Dr Roberts.

.jpg?sfvrsn=cc9a5140_3)

Julian was born in Penketh, Cheshire in 1925. He spent his childhood between Penketh, Liverpool and Dolgellau in North Wales, with most of his secondary education being at Prescot Grammar School near Liverpool. He excelled at school and was encouraged to apply for a medical degree. He chose Edinburgh University, where again he excelled academically.

During his final year in Edinburgh he spent time at Preston Royal Infirmary, where he met his future wife, Edna, who was a nurse there. They were married in 1946. After completing his degree he moved to Wakefield as an Assistant Medical Officer at Stanley Royd Hospital. On the advice of the Physician Superintendent, Dr Cooper, he enrolled to study for a Diploma in Psychological Medicine at Leeds University.

After passing this course he was called up for National Service and sent to the Royal Victoria Military Hospital at Netley, Southampton. There he found many patients who would now be described as suffering from PTSD but were then said to be ‘battle weary’. He was about to be posted to Korea but failed the medical and was discharged from the Army. After working at Portsmouth for a year he realised he needed further professional qualifications to progress and so accepted a post as Senior Registrar at Leeds University Department of Psychiatry, where he could concentrate on obtaining his MD. He worked with Professor Max Hamilton whilst in the department and assisted him with his research into depression, which led to the publication of the Hamilton Rating Scale, still in use today.

In 1960, after completing his MD, he was appointed as Consultant Psychiatrist at St James’ Hospital in Leeds, where he stayed until his retirement. He was made a Foundation Fellow of the Royal College of Psychiatrists when it formed in 1971. In 1970 he was appointed to the Regional Health Authority where he spent 12 years helping to develop psychiatric services in the Yorkshire region. He was the first RCPsych Regional Advisor for Yorkshire. He was also asked to be a member of several NHS hospital Inquiries, the highest profile being at Rampton High Security Hospital, of which he became acting chairman.

Although he retired from clinical practice in 1989 he continued working as a Lord Chancellor’s Visitor and as a member of the Parole Board until full retirement in 1995. He was awarded an OBE for his contribution to psychiatric services in 1988.

In retirement he particularly enjoyed walking, visiting old churches, genealogy and botany. His wife died in 2017 after more than 70 years of marriage and he then lived alone, supported by their 4 children, 6 grandchildren and 14 great grandchildren. He died in 2024.

His long life enabled him to witness enormous changes and progress in the development of psychiatry. On a personal level he was able to adapt and contribute to these changes and his kindness, compassion and care for his patients were exemplary. His personal contribution towards the development of psychiatry in Yorkshire was immeasurable.

Obituary by Professor Alan Eppel, nephew of Dr Abrahamson.

.jpg?sfvrsn=1b5bf167_7) Dr David Abrahamson MBE FRCPI FRCPsych

Dr David Abrahamson MBE FRCPI FRCPsych

David Abrahamson was born in Dublin under rather remarkable circumstances. He was the second of a pair of very premature twins delivered with great difficulty at the Portobello Nursing Home. Some days after the delivery there was a fire in the building. David, his twin brother Max, and their mother had to be rapidly evacuated. At home the twins were kept in shoeboxes inside a chest of drawers! Incubators were not available! David always recounted this story with a sense of resilience. David was the fifth child of Tillie and Leonard Abrahamson.

Before qualifying as a physician at Trinity College Dublin David had practised as a veterinarian. His interest in psychiatry was piqued when, as a senior house officer at the North Middlesex Hospital, he was impressed with the sense of camaraderie among the psychiatric patients. This was one of the factors that led him to appreciate the importance of social networks In 1960 he became a senior registrar at the Maudsley Hospital in London. This was during the time when Aubrey Lewis was Chair of Psychiatry. David came to believe that there was too much distance between psychiatrists and their patients. This often diminished the essential humane nature of the treatment relationship.

He was appointed as a consultant at the Goodmayes Hospital in East London. There he had responsibility for two acute inpatient units, one unit for 'disturbed' patients and three hundred long-stay patients. He was highly committed to the NHS and refused to engage in any form of private practice. He undertook detailed research of 491 long-stay patients at Goodmayes. He demonstrated that many of these patients did not exhibit much deterioration from the time of their admission and had long stable periods. This indicated to him the potential for rehabilitation and resettlement.

David was successful in moving long- stay patients into the community. Of prime importance in his approach was working with a multidisciplinary rehabilitation team and with local housing authorities. He and his team succeeded because they did not treat long stay patients as 'second class'. He had demonstrated that most patients did not have a progressive decline. He recognised the existence of meaningful social networks on long stay units and the importance of maintaining these when moving into community housing.

Over the ensuing three decades multiple housing units with varying formats were established in collaboration with housing authorities. He discovered that when long stay patients moved into supported housing they missed their friends from the wards even when these patients were unable to speak. David and his team set up a weekly social club which he attended. It was for his work with long stay patients and their move into community housing that he was awarded the MBE in 2002.

He was beloved by his family and devoted to his wife Valerie of 60 years. Valerie had been a ballerina with the Royal Ballet and the Festival Ballet companies and taught dance for several years. As well as a having a brilliant intellect, David had a subtle dry wit which never failed to entertain at family gatherings and celebrations. He took great interest in his daughters’ careers and was an inspiration to them. Leonie worked at the Anna Freud Centre in London and has taught Early Childhood Education. She is the author of 'The Early Years Teacher’s Book'. Vanessa has had a distinguished academic and research career in applied Health and Social Care research, very much in line with her father’s vision.

David Abrahamson was a physician possessed of great humanity, intellect, and compassion. He was dedicated to the care of the most seriously psychiatric ill patients. He made their lives better.

Obituary by Susan Merskey, widow of Dr Merskey.

.jpg?sfvrsn=ab557c31_3) Dr Harold Merskey DM FRCP FRCP(C) FRCPsych

Dr Harold Merskey DM FRCP FRCP(C) FRCPsych

Harold Merskey, who died on May 15, 2024 of vascular dementia, was born and brought up in Sunderland. For nearly 60 years, Harold was an exemplary psychiatrist and pain management specialist. He was internationally renowned for his work in pain management and contributed greatly to other areas such as false memory syndrome, hysteria and dementia.

His early research interests grew out of his work with individual patients. He saw that helping patients whose chronic pain was ignored because it was in soft tissue was paramount, whether through research to establish better prescribing methods or assistance to reach decent settlements from insurance companies after motor vehicle accidents. Harold’s commitment to patient care and scientific research advanced the study and treatment for pain, and our understanding of dementia.

As a young man, he wrote the definition for pain which remained in use for decades. Author of more than a dozen volumes, and 400 publications, Harold was a prodigious writer, a fine teacher, a mentor and colleague to friends around the world and across several generations. People reached out to him regularly; they relied on his discretion, his wisdom, and his compassion. In the broader community, Harold was proud to help combat the abuses of psychiatry and speak out on behalf of political and religious dissidents trapped in the former Soviet Union in the 1960s to 1980s. Privately and professionally, he was always willing to speak up for those who could not speak for themselves.

Harold qualified in Medicine from Oxford University in 1953. He started his psychiatric training during his National Service, before gaining his Diploma in Psychological Medicine and becoming a Members of the Royal Medico-Psychological Association. He held positions in Sunderland, Sheffield, Nottinghamshire and the then National Hospital for Nervous Diseases in London, before moving to London, Ontario in 1976 as Director of Education and Research at the then London Psychiatric Hospital and a Professor in the University of Western Ontario’s Department of Psychiatry.

Harold was a founding member of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) and of the Canadian Pain Society where he served as President (1988-1991). He was the first Chair of IASP’s International Pain Classification Committee and founding Editor-in-Chief of Canadian Pain Research and Management. He was a founding Member, later, a Fellow, of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, and a Fellow of the Royal Colleges of Physicians of both England and Canada.

Harold’s work was recognized with a Lifetime Achievement Award and a Distinguished Career Award from the Canadian Pain Society. In 2016, he received an Honorary Doctorate from the University of Western Ontario.

Harold was a devoted and loving family man. Married to Susan for fifty-nine years, he was immensely proud of their three children and five grandchildren’s achievements. He enjoyed spending time with family members and they with him; each one has their own special memories of those times.

Obituary by David St Clair and Robert Wrate, friends and colleagues of Professor Whalley.

Professor LJ Whalley MBBS MD DPM FRCP(E) FRCPsych, born 3 March 1946, died Edinburgh 11 April 2024

Professor LJ Whalley MBBS MD DPM FRCP(E) FRCPsych, born 3 March 1946, died Edinburgh 11 April 2024

Born in Lancashire, one of five children, Lawrence was educated at St Joseph’s College in Blackpool. His intellectual curiosity, partly inspired by the teaching brothers, continued undiminished thereafter. After graduating in medicine from Newcastle University and postgraduate psychiatric training in Edinburgh, including an MD in 1976, he was for eight years Senior Clinical Scientist at the MRC Brain Metabolism Unit in the Royal Edinburgh Hospital; there Lawrence along with fellow consultant psychiatrist Dr Janice Christie directed a clinical psychiatric neuroendocrine research programme with special emphasis on major affective disorders. He developed during this time a parallel interest in dementia, and observed that early-onset cases seemed to cluster in the community. After a short period as senior lecturer in psychiatry in Edinburgh, in 1988 he accepted the Crombie Ross Professorship in Mental Health at the University of Aberdeen.

Not long after moving to Aberdeen University Lawrence and his wife Patricia, who was a teacher, discovered an epidemiological gold mine as in 1932 and 1947 all pupils in Scotland aged eleven were IQ tested and the records archived by the Scottish council for research in education. Permission was granted to access these long forgotten records of around 150,000 one-time eleven-year-olds for medical research. Then began a series of ground breaking follow up studies of the original eleven-year-olds. With key involvement of Edinburgh collaborators Professors Ian Deary and the late John Starr, it became possible in both Aberdeen and then in Edinburgh to trace most of these individuals, and if still alive obtain their consent to be re-examined using modern methods; this allowed a life-course approach to understanding brain health and cognitive decline in later life. It emerged that lower eleven-year-old IQ predicted both increased life-time morbidity and mortality (e.g. by lung cancer) independent of social class, together with enhanced decline in higher cognitive functioning.

A prestigious Wellcome Trust Professorial Fellowship (2001-2006) allowed him to pursue his academic research work full time; this included writing for lay readership The Ageing Brain (2001, 2004). Lawrence published prodigiously throughout his career and retirement, including at least 300 scientific papers and seven books.

Lawrence married his first wife Patricia as a medical student; they had three daughters; he married his second wife Helen while based in Aberdeen. Although more than fifty years in Scotland, Lawrence remained proud of his Lancashire roots, and he never lost his accent. Underlying his direct way of speaking and sometimes brusque manner lay a complex emotional man for whom personal relationships were extremely important, most of all with his large circle of family members.

He will be remembered not only for his academic dedication and outstanding achievements, but for his character, full of energy, generosity and loyalty to friends, family members, and colleagues both academic and NHS.

He is survived by his two ex-wives Patricia and Helen, his three daughters, three stepchildren and six grandchildren.

Dr Parkes died peacefully at home on 13 January 2024, aged 95 years.

You can read an obituary about his life and work on the Guardian's website.