Finding Ivy: A Life Worthy of Life. An exhibition at RCPsych Prescot St, 17 February-12 May 2026

17 February, 2026

By Dr Claire Hilton, Honorary Archivist at the RCPsych.

Brighton, Nottingham, Lambeth, Leytonstone, Chester, and Broughty Ferry in Scotland—towns, villages, cities and suburbs in the UK—close to home for many of us, are not usually associated with victims of the Holocaust. Yet some people born in these places were among those systematically murdered by the Nazis in their so-called ‘euthanasia’ programme. Typically, with one or both parents from Germany and/or Austria, they had relocated from the UK to those countries with their families. There were numerous reasons for doing that, including hostility towards non-combatant Germans in the UK during and after the First World War.

The Nazi euthanasia programme was known as ‘Aktion T4’, ‘T4’ being short for Tiergartenstrasse 4, the address in Berlin from where the operation was masterminded. Aktion T4 resulted in the systematic murder of around 70,000 people between 1940 and 1941. It aimed to rid the country of people perceived as being ‘unworthy of life’ because they required support in daily activities and were considered unable to contribute to society. There was also the fear that many had hereditary conditions and the Nazis wanted to prevent transmission to future generations. Based on eugenic ideology, the Nazis used the term 'racial hygiene'.

Some people living in Germany under the Third Reich voiced their objection to the T4 programme, which led to it being scaled back. However, by then the Nazis had learnt much from it, knowledge later employed in the Holocaust to murder Jews, gay men, Sinti, Roma and other groups of people. Things they learnt included that: deception—such as telling people they are being evacuated or re-settled—could ensure calm; and having killing centres in occupied lands rather than within the Greater German Reich might avoid opposition. They had also perfected killing by gassing.

Finding Ivy: the exhibition, and learning from it

British-born Ivy Angerer was among those murdered. Finding Ivy is dedicated to her memory. It tells the story of her life, and the lives of a dozen other victims. It is based on the research of Dr Helen Atherton, a learning disability nurse and historian in the School of Healthcare, University of Leeds, and Dr Simon Jarrett, a visiting research fellow at the Open University, along with international researchers from across Germany and Austria. Helen’s team traced and worked collaboratively with the families of those murdered, including Dr Nancy Jennings, a UK based biologist, whose great uncle Zdenko Hoyos was among them. In commemorating the lives of these victims of Nazi atrocities, the exhibition also encourages us to critically reflect on our own attitudes, beliefs and behaviours towards marginalised and devalued people.

Ivy Angerer. (Credit: Dokumentationsstelle Hartheim/Lern- und Gedenkort Schloss Hartheim)

Not only are the places some of the victims came from uncomfortably close to home geographically, but since a large proportion selected for death were labelled as having long-term mental conditions of various kinds, they are also close to our professional concerns as psychiatrists. What is more, the term ‘life unworthy of life’ comes from the title of a pamphlet published in 1920 (original in German): Permitting the Destruction of Life Unworthy of Life. One of the authors, Alfred Hoche, was a psychiatrist. Psychiatrists and psychiatric nurses were also involved in the killings.

In addition to geography and psychiatry, there is another uncomfortable closeness: eugenics. Eugenics means ‘good birth’, and its advocates sought, usually by institutionalisation or sterilisation, to prevent the birth of people with characteristics regarded as less favourable, or predisposed to acquire them. Eugenics was not a Nazi creation, but it germinated in England, invented by Sir Francis Galton (1822-1911) who worked at University College London. It was rooted in Victorian ideologies of classism, racism and ableism.

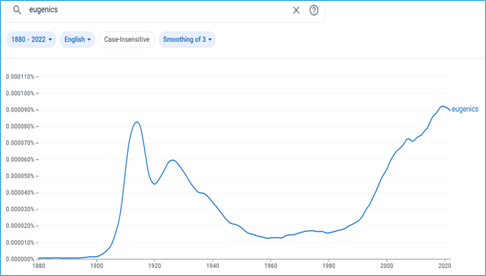

One might ask ‘Surely this is all in the past now?’ Sadly, I think not. Our scientific understanding today is different, but eugenics was an ideology rather than a science, and it does not seem to be far from the surface. A very rough and ready estimate of the frequency of use of the word ‘eugenics’, suggests an increasing interest in the subject. Derived from the corpus of digitised books in English, the Google Books Ngram Viewer search engine found that ‘eugenics‘, as a percentage of total words searched, reached a peak just before the First World War, then declined in use, but its frequency has increased about 8-fold between 1960 and today. In a recent lecture, evolutionary behavioural scientist Professor Rebecca Sear, said that eugenics is ‘a coercive ideology. It involves people in positions of power making value judgements about which traits are desirable or not, and so who is deserving of reproduction or not, and it inevitably leads to human rights abuses.’

Ngram Viewer (screenshot): change in frequency of use of word 'eugenics', 1880-2022. Made by Claire Hilton and used with her permission.

After the Second World War, some doctors and nurses were sentenced to death for their part in Aktion T4. Others argued that they were following orders and were acquitted. Challenging orders is an important matter in healthcare today: do we question sufficiently what we are told to do? Do we follow care-pathways in an unthinking way? At times, when interests conflict, do we show more allegiance to our employer’s instructions or to the needs of our patients’ as individual human beings?

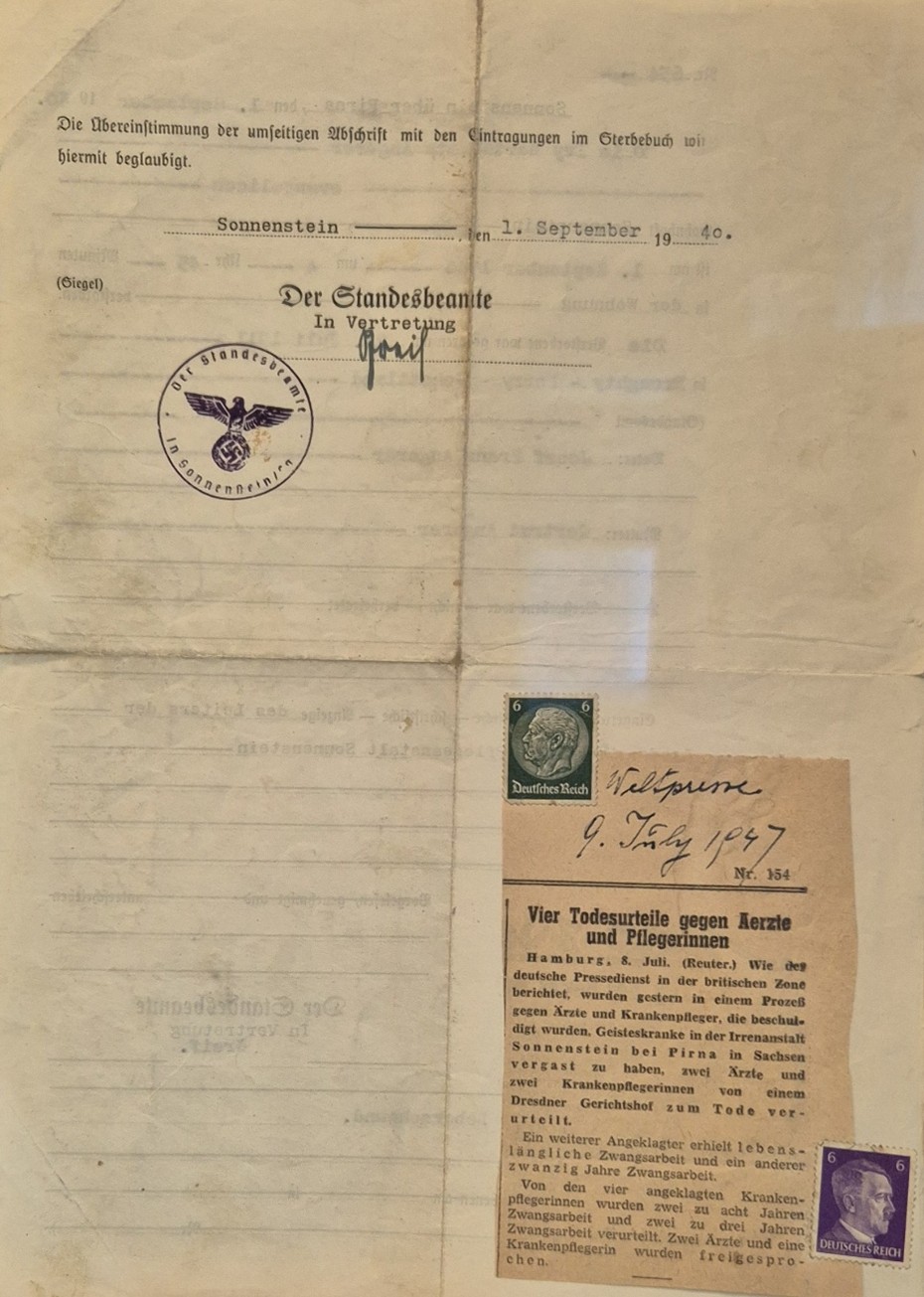

Many people never knew for sure the fate of their relatives who suffered from some sort of long-term mental or physical condition and died unexpectedly during the war. Ivy’s death certificate was found among her father’s belongings after he died. The cause and place of death stated on it were false, as confirmed by recent research. As in the photograph below, a newspaper cutting affixed to the back of it suggests that Mr Angerer was dubious about the information sent to him, suspected his daughter’s true fate, and lived with that pain for the rest of his life.

Reverse of Ivy Angerer’s death certificate sent to her father in 1940, with newspaper cutting attached. (Credit: Dokumentationsstelle Hartheim/Lern- und Gedenkort Schloss Hartheim)

Acknowledgements: I am grateful to Helen Atherton, Jacob Hilton and Fiona Watson for their comments.